areppim: information, pure and simple

ITU (International Telecommunications Union) estimates that by the end of 2018 there were 8.2 billion mobile subscribers worldwide, corresponding to a global penetration of 95%. This averages 10.7 mobile phones for 10 people, or almost two active devices per living person.

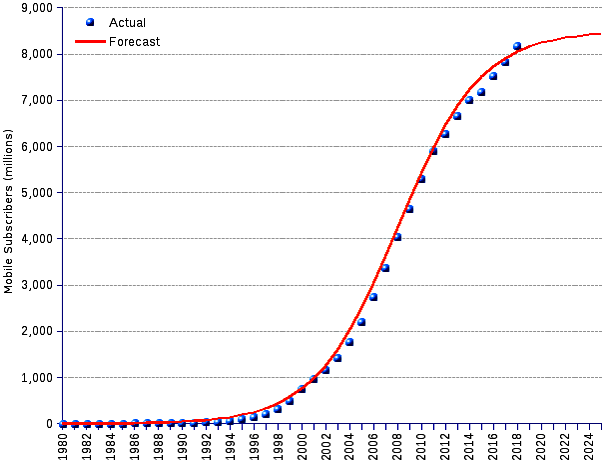

Our new forecast (compare with 2017, 2013, 2012, 2011, and 2008 forecasts) shows ITU's data of actual mobile subscriptions from 1980 through 2018, represented by blue dots, and areppim's forecast till 2025, represented by the S-shaped red line. The model anticipates a global market size of 8.4 billion subscribers by 2025, at 99.3% of saturation (estimated at 8.5 billion), or the equivalent to 104% of inhabitants.

Global mobile subscribers have grown much faster than population. However, as indicated in the table below, growth slows down significantly in the developed countries (3.8%), while it fares faster in the developing countries (13.8%). Until 2008, when it reached its midpoint, subscribers grew at the annual rate of 54.7%, doubling in size every 1.6 years. Thereafter, from 2009 to 2018 the rate slowed down to only 6.47%. As the market matures, approaching saturation, population growth (0.94% annually from 2019 to 2025) overtakes subscribers growth (0.56%), causing the percent of active subscribers to the population to drop from the current 107% to 104% in 2015, to eventually decline to 100% or 101%, or about one subscriber per living person.

The people's need to communicate fed the mobile's boom has it had already driven the success of its fixed-line phone ancestor. The convergence of telephony and Internet bolstered its organic growth, augmenting its basic telephony capability with the myriad of functionalities that we all know. The strides made by the plain 1995 cell phone to become the high-performance, multi-purpose 2018 smart phone, more powerful and more skilled than the traditional personal computer, are awesome. Mobiles can make you a dinner reservation, find a taxi, guide you in the city's maze, exhibit your transportation ticket, pay your purchase, prove your id, find a dog walker or even arrange your dry cleaning. One wonders how could the 20th century person survive without such crucial helpers.

Taking the number of subscribers as a proxy for the number of phone devices provides only an approximation. Joe Smith may have three or four subscriptions for one single cell phone. One for his personal calls, another for professional calls, a third for use in a country where he travels frequently, one more for his home alarm system, etc. Be it as it may, one can take for sure two broad statements. Number one, there is a really huge number of mobile phones out there. Number two, the market approaches saturation, the planet is not large enough to ingurgitate many more devices. This is surely a major concern for mobile constructors and marketers who scratch their heads to try and guess what should they do next lest their business collapse.

Big phone companies are already feeling the crunch. Beginning of January 2019, Apple dramatically lowered its sales revenue projection due to sluggish iPhone demand. The day after, within a few hours, the stock price of Apple plunged by nearly 10 percent. The South Korean Samsung is also struggling to cope with declining sales. Smart phone sales have stopped growing. Users feel less compelled to acquire new models, as they don't find in them any changes worth the expense. This is a bad omen for smart phone manufacturers who could continue to see a slump in sales throughout the years to come.

Forget the manufacturers. Should the deluge of mobile phones be a concern also for the average person, likely a regular subscriber and owner of a mobile device? The answer is a double yes: the great heap of phones matters for everyone, whether or not a mobile user. We gloss over the human issues raised by the authentic mobile phone addiction of many users, fostered by millions of savvy communicators keen on influencing to their and their patrons' benefit the attitudes, preferences, desires, fears, longings, cravings and wants of the crowds.

Whatever the noxious effects of the addiction on the human psyche, the social sequels are especially worrisome. The stealthy spreading of the technology to an increasingly vast field of social interactions is building a relentless information cobweb around each person, sensing, tracking, interpreting and recording each and every step, whether the user is actively using, or just carrying a dozing device. A growing number of instances, from public services to banks, ticket offices, utility companies, health care centers, commercial enterprises, etc. are making the ownership of a mobile subscription a default prerequisite to process their dealings, gradually substituting virtual to hard transactions. In the process, they capture and register all that is to be known about the counterpart. This intrusive prying into one's private affairs, carried out without proper control by the subject, often filed and sold subreptitiously to unauthorized third parties, eventually leads to raping one's privacy, exposing one's innermost self, spying one's most innocent moves, recording one's casual thoughts, in short dissolving one's freedom.

The truth is that today's mobile phones are exceptionally handy spying artifacts. How can we be sure? Simple — the U.S. administration says so, the Chinese and a handful of other government suggest so. The Chinese Huawei is the second largest smart phone maker in the world behind Samsung and before Apple, and a leader in 5G wireless technology. But Huawei is allegedly much more than that. It is a mammoth espionage agency. The company's smart phones, according to FBI Director Christopher Wray, can be used to

Not only that. maliciously modify or steal information,

as well as conduct undetected espionage.

Earlier this year the Pentagon banned the devices from all US military bases worldwide.The new superfast 5G networks, which are 100 times faster than 4G, will literally run the world of the future. Everything from smart phones to smart cities, from self-driving vehicles to, yes, even weapons systems, will be under their control. In other words, whoever controls the 5G networks will control the world.

So much for the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, article 12, stating that No one shall be subjected to arbitrary interference with his privacy, family, home or correspondence (...). Everyone has the right to the protection of the law against such interference or attacks.

Those rambling billions of mobile phones have many other nefarious effects, before and after their useful life span. One should consider their full life cycle, from the raw material extraction, through material processing, manufacturing, use, and final waste disposal. What is their imprint on the depletion of natural resources, and on the preservation of healthy natural surroundings?

The demand for electronic goods, which for many people represent a higher standard of living, is expected to keep growing, even if at a lower speed in some instances. The trend is supported by the harsh competition in the telecommunication markets that brings down the prices of services and devices, as well as by the advances in computing power, mobile broadband technologies, and component design. More people can afford purchasing new technology. As a consequence more equipment will be eventually thrown away. The trend is boosted by the consumerist behavior consisting of discarding old devices and buying new ones instead of keeping or repairing. The average smart phone life time in China, U.S.A. and major European countries is in the 18 months to 24 months brackets. This could mean that the 8.2 billion mobile phones in existance may soon multiply.

Contrary to their modest and clean demeanor, electronic devices are actually voracious and foul. A researcher at the United Nations University in Tokyo measured the elements needed to make a 2-gram chip. It takes 1.7 kg of fossil energy, 1 m³ of nitrogen, 72 grams of chemicals and 32 liters of water. By comparison, it takes 1.5 tons of fossil energy to build a 750 kg car. The ratio of the energy input to build the car is 2 to 1, while for the chip it is 630 to 1. The demure micro-chip, so frugal in appearence, has in fact a gargantuan appetite.

In addition to chips, a modern mobile phone may contain 500 to 1,000 different components necessitating a wide group of raw materials, for instance coltan (for capacitors), gold (connections), indium (screens) , gallium (LEDs), germanium (WiFi), antimony (battery plates), etc. The European Union, concerned about the sustained supply of what they name Critical Raw Materials, of which they identified 27 in the 2017 exercise, reports that some of these elements will be particularly sought after by the leading industries. The future global resource use could double between 2010 and 2030, (...) the demand for certain raw materials [is expected to increase] by a factor of 20 by 2030.

.

The surging demand exerts much strain on the extraction of metallic ores. The global quantity extracted rose from 3.72 billion tons in 1980 to 5.8 billion tons in 2002 and is expected to reach 11.14 billion tons in 2020. If the populations of the emerging countries adopted technologies and lifestyles similar to those prevailing in the OECD countries, the global demand for metals would be 3 to 9 times greater than the amount of metals currently used in the world.

Developing countries are struggling with the environmental effects of increased extraction rates. Huge volumes of waste and wastewater; air, water and soil pollution and contamination; release of hazardous chemicals and materials; dissipation losses. Not to speak of the scramble for resources responsible for many wars, violence, forced labor and population exodus in the mineral-rich areas of Africa, South America and Asia.

As global demand for many metals continues to rise, more low-quality ores are mined, leading to an overall decrease in ore grades. Although the extraction methods continue to improve, the mining of lower-grade ore using techniques such as open pit mining and ultra-deep mining (from 5 to 6,000 meters below the surface) entails massive earthmoving for the same ore extraction. The cost is a huge scale soil disruption, water use and pollution, and energy consumption. To provide an order of magnitude, it takes the gold miner Barrick an average of 2.31 tons (spread from 75 kg to 5,704 kg) of rock to produce just 1 gram of gold. Think of the 11.14 billion tons of metallic ores expected to be needed by 2010. Apply the 2.31 tons to 1 gr ratio, or whatever ratio of your preference, and you will get the sinister representation of the tearing of the planet to tatters required to feed the industry.

In order to supply the world with the much-wanted metallic ores, mining enterprises have launched underwater sea-bed prospecting projects. To turn a profit, companies would need to collect three million metric tons of dry nodules a year, yielding about 37,000 metric tons of nickel, 32,000 metric tons of copper, 6,000 metric tons of cobalt and 750,000 metric tons of manganese. A varied array of life at a scale of 50 microns or larger live on the nodules or in the sediment. Most of these creatures will die from the scouring or be smothered by the sediment cloud as it settles. Given that nodules take millions of years to form and that biological communities are very slow to develop, harvested regions are unlikely to recover on any human time-scale. If only 30 percent of a nodule is desirable metals, 70 percent is waste, typically a slurry. Slurry from millions of ocean nodules will be new material that has to go somewhere.

Continents and oceans, the quest for mineral ores will leave no stone unturned — the ubiquitous mobile phone gladly participates in the onslaught.

Leaping through the manufacturing and the use phases, let us take a glance of the disposal phase. Discarded mobile phones are part of e-waste. The global quantity of e-waste generated in 2016 was around 44.7 million metric tonnes (Mt) or 6.1 kg per inhabitant. In 2017, the world e-waste generation will likely exceed 46 Mt. The amount of e-waste is expected to grow to 52.2 Mt in 2021, with an annual growth rate of 3 to 4%.

Increasing volumes of electronic waste raise two big concerns. An environmental one, because its improper and unsafe treatment and disposal through open burning or in dumpsites, pose very serious risks to the environment and human health. An economic one, because the total value of all raw materials present in e-waste, most of which are just thrown-away, is estimated at 55 billion Euros (60 billion USD) in 2016. To address such pressing issues, regulators developed standards and procedures for e-waste triage, collection, take-back, recycling, and final disposal. However, available statistics show only lack-luster results.

Only 20% (8.9 Mt) of e-waste generated worldwide in 2016 is documented to be collected and properly recycled. The remaining 80% (35.8 Mt) of e-waste is not documented. Approximately 76% (34.1 Mt) of e-waste is untraced and unreported, probably dumped, traded, or recycled under substandard conditions. In the higher income countries, 4% (1.7 Mt) of e-waste is thrown into the residual waste.

How much do discarded mobile phones weigh in the mass of e-waste? Impossible to tell, surely far too much. Which leads to the logical deduction that, in addition to the convenient communications device that they unequivocally are, mobile phones hide the deceitful and malevolent features of an effective instrument to enchain the people's minds, to reduce social relationships to crumbs, to deplete nature, and to poison soil, water, air, and ravage the human health. The challenge is: how much longer will mobile phone makers be tolerated to produce devices with a lifespan of 18 to 24 months, whereas they should last for 18 to 24 years?

| Year | World | Developed Countries | Developing Countries | Forecasts ¹ World | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (millions) | (% of inhabitants) | (millions) | (% of inhabitants) | (millions) | (% of inhabitants) | (millions) | (% of inhabitants) | |

| 1980 | 0.02 | 2.56 | 0.06 | |||||

| 1981 | 0.06 | 3.42 | 0.08 | |||||

| 1982 | 0.10 | 4.57 | 0.10 | |||||

| 1983 | 0.15 | 6.11 | 0.13 | |||||

| 1984 | 0.32 | 8.16 | 0.17 | |||||

| 1985 | 0.75 | 10.89 | 0.22 | |||||

| 1986 | 1.45 | 14.54 | 0.29 | |||||

| 1987 | 2.55 | 19.42 | 0.38 | |||||

| 1988 | 4.33 | 25.92 | 0.50 | |||||

| 1989 | 7.35 | 34.58 | 0.66 | |||||

| 1990 | 11.21 | 46.13 | 0.87 | |||||

| 1991 | 16.00 | 61.51 | 1.1 | |||||

| 1992 | 23.00 | 81.96 | 1.5 | |||||

| 1993 | 34.00 | 109 | 2.0 | |||||

| 1994 | 56.00 | 145 | 2.6 | |||||

| 1995 | 91.00 | 193 | 3.4 | |||||

| 1996 | 145 | 256 | 4.4 | |||||

| 1997 | 215 | 338 | 5.7 | |||||

| 1998 | 318 | 445 | 7.5 | |||||

| 1999 | 490 | 585 | 9.7 | |||||

| 2000 | 738 | 763 | 12.5 | |||||

| 2001 | 961 | 990 | 16.0 | |||||

| 2002 | 1,157 | 1,272 | 20.3 | |||||

| 2003 | 1,417 | 1,618 | 25.5 | |||||

| 2004 | 1,763 | 2,032 | 31.6 | |||||

| 2005 | 2,205 | 33.9 | 992 | 82.1 | 1,213 | 22.9 | 2,512 | 38.6 |

| 2006 | 2,745 | 41.7 | 1,127 | 92.9 | 1,618 | 30.1 | 3,053 | 46.3 |

| 2007 | 3,368 | 50.6 | 1,243 | 102.0 | 2,125 | 39.1 | 3,639 | 54.5 |

| 2008 | 4,030 | 59.7 | 1,325 | 107.8 | 2,705 | 49.0 | 4,250 | 62.9 |

| 2009 | 4,640 | 68.0 | 1,383 | 112.1 | 3,257 | 58.2 | 4,860 | 71.1 |

| 2010 | 5,290 | 76.6 | 1,404 | 113.3 | 3,887 | 68.5 | 5,446 | 78.7 |

| 2011 | 5,890 | 84.2 | 1,406 | 113.1 | 4,483 | 78.0 | 5,987 | 85.6 |

| 2012 | 6,261 | 88.5 | 1,443 | 115.7 | 4,817 | 82.7 | 6,467 | 91.3 |

| 2013 | 6,661 | 93.1 | 1,479 | 118.2 | 5,183 | 87.8 | 6,881 | 96.1 |

| 2014 | 6,996 | 96.7 | 1,527 | 122.0 | 5,468 | 91.4 | 7,227 | 99.8 |

| 2015 | 7,181 | 97.4 | 1,563 | 125.2 | 5,618 | 91.7 | 7,509 | 102.5 |

| 2016 | 7,511 | 100.7 | 1,587 | 126.8 | 5,924 | 95.5 | 7,736 | 104.5 |

| 2017 | 7,814 | 103.6 | 1,594 | 127.0 | 6,220 | 99.0 | 7,914 | 105.7 |

| 2018 ² | 8,160 | 107.0 | 1,616 | 128.0 | 6,545 | 102.8 | 8,054 | 106.5 |

| 2019 | 8,161 | 106.8 | ||||||

| 2020 | 8,243 | 106.8 | ||||||

| 2021 | 8,306 | 106.6 | ||||||

| 2022 | 8,354 | 106.2 | ||||||

| 2023 | 8,390 | 105.7 | ||||||

| 2024 | 8,417 | 105.1 | ||||||

| 2025 | 8,437 | 104.4 | ||||||

| 2026 | 8,453 | 103.7 | ||||||

| 2027 | 8,464 | 102.9 | ||||||

| 2028 | 8,473 | 102.2 | ||||||

| 2029 | 8,480 | 101.4 | ||||||

| 2030 | 8,484 | 100.7 | ||||||

| Average annual change rate | 40.5%: 1980-2018; 6.5%: 2009-2018; 10.6%: 2005-2018. | 3.8% | 13.8% | 19.7% | ||||

| ¹ Logistic growth function. Parameters: Saturation M = 8,499 million; Midpoint tm = 2008; Growth time Δ t = 15.18.

² ITU's estimates. | ||||||||

Source: ITU-International Telecommunications Union