areppim: information, pure and simple

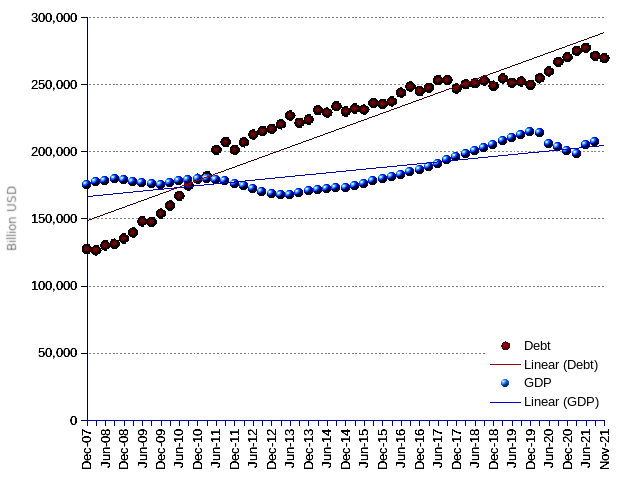

It had to happen, the coronavirus did it. The Portuguese economy started its journey into hell, courtesy of the Covid-19 pandemic. After the World Health Organization declared the pandemic on March 11, 2020, all the red lights started flashing. The government debt, out of control as usual, has been boosted to a new historical peak of 137.2 percent of GDP in March 2021. Not to soften the state of affairs, GDP took a nose dive in the context of a general economic crisis. In 2020 it plunged by 7.6 percent relative to 2019. Thereafter, it has followed a bumpy trail and the prospects are anything but rosy.

No need to consult a clairvoyant to prognose a widening gap between the fast climbing debt and the declining GDP. Eventually, when the EU (European Union) and the ECB (European Central Bank) reinstate the abhorred Maastricht criteria, currently set aside, pandemic obliges, no accountancy trickeries by the ministry of finance will safeguard taxpayers from feeling the pain.

The government will have a hard time to finance the debt service in the context of an already heavy tax burden, and with an economy coming to a stop. As the country’s indebtedness increases, the financial markets will impose heavier spreads sooner or later. Meanwhile, the tax revenue generating economy will hardly benefit from the easy money provided by the ECB and the EU, which, as it always happened before, will lubricate the big finance (facilitating the clean up of the balance sheets, creating stockholder value through the purchasing of own stock, debt restructuring and other financial operations by large companies), avoiding like the plague the uncertainties of investing in the productive economy.

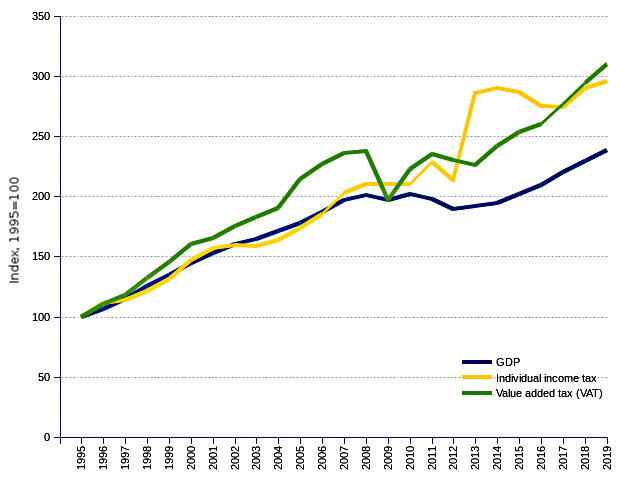

Portugal's tax burden continues rising in absolute values, while stabilizing at 37 percent of GDP. In the recent years of the alleged post-austerity policy the overall fiscal burden grew faster (4.35 percent) than GDP (4.25 percent).

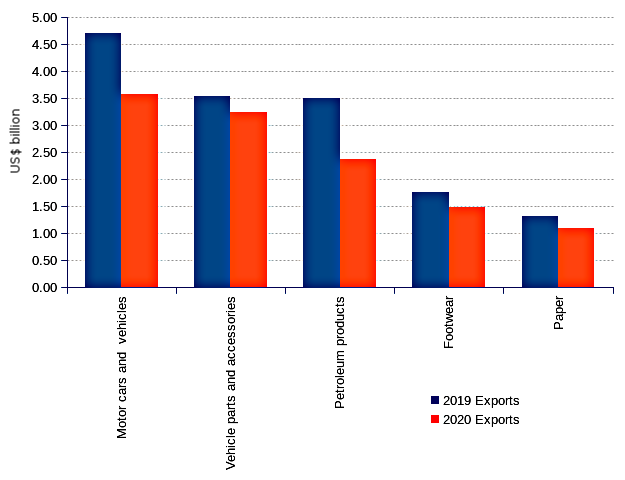

For an economy like the Portuguese, with a small internal market and far from being self-sufficient, external trade is of critical importance. The country relies on the international markets, mostly the EU, to provide an outlet for its goods and services. It is also in the EU that it procures the food and other staples to keep people going, as well as materials, accessories and parts to feed its industrial operations. Unfortunately, things are going down the drain. In 2020, exports recorded a year-on-year negative change of -20 percent, while imports fell by -15 percent. In lay terms, the country is unable to find customers for its goods and services, and therefore it needs only a reduced amount of pieces, parts and materials to feed its idling manufacturing capability.

A quick analysis of the bigger money-making export categories illustrates vividly the predicament. The country’s top five exports are Motor cars and vehicles, Vehicle parts and accessories, Petroleum products, Footwear and Paper, representing a total of US$ billion 15.91 (or 23.75 percent of total exports) in 2019.

The column chart offers a striking view of the disaster. The main export categories crashed in April 2020 and ended the year well below the 2019 values.

In 2020, all the five main export categories show huge negative changes, totaling a -25 percent change for that merchandise group.

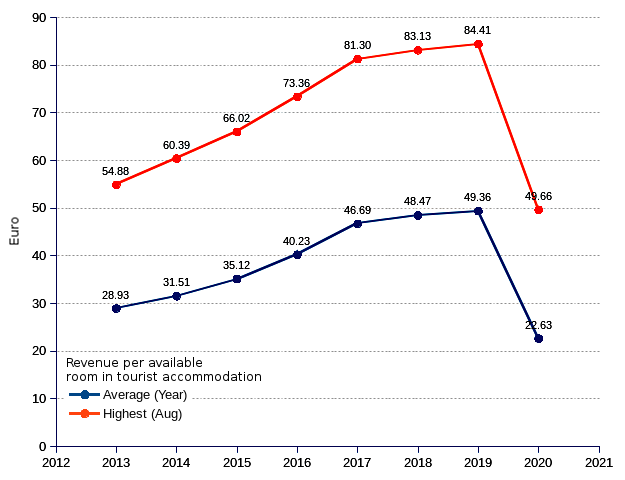

Another milk cow of the Portuguese economy has been tourism. The Covid-19 killed it overnight. Picking just two variables of the tourism business, we see that the passenger flow traffic in the Portuguese airports fell by -69.4 percent in 2020, compared to 2019. Airports are empty, but so are the rooms for tourist accommodation. The average revenue per available room in tourist accommodation casts a dramatic light on the industry debacle.

After growing at an average rate of 9.32 percent per year from 2013 to 2019, revenue per room for tourist accommodation stumbled by -54.15 percent in 2020.

By early 2019, the prime minister guaranteed that the austerity

program of the Troika period (imposed in 2011 by the International Monetary Fund, the EU and the ECB) was a thing of the past, never to come back till kingdom come. He might be frightfully right. The pandemic brings a string of lean years ahead, such that the government, with only a narrow range of responses in its recipe book, will be forced to resort not to an austerity, but to an outright grimness

economic policy.

Hereinafter, you find our former brief on the Portuguese debt, where we pointed the structural weaknesses of an economy that gets away with industrial assembly and subcontracting, harmful tourism and financial juggling.

Portuguese government debt (Maastricht debt) keeps riding significantly ahead of Portugal's GDP (gross domestic product), especially since June 2011, when right-wing Coelho took office as prime minister. The socialist Costa did not perform much better since he took over on November 2015. After one year of rollercoaster, government debt reached a peak in May 2019, then subsided by more than two percent by June 2019, only to resume its sharp fluctuations thereafter. Since the beginning of 2020, it went significantly up reaching its highest value ever in Februay 29th, while GDP is expected to be falling at a rapid pace due to the economic consequences of the coronavirus pandemic. It is a cinch to predict that future data releases will expose a widening gap between the two variables.

Past improvements were rooted more in the realm of creative accountancy rather than in a truthful account statement — indeed, the trade of today's finance ministers, further to pressing the paxpayer for an extra dime, consists also of surreptitiously hiding unfortunate obligations in the closet, while dangling eyewash resources in front of the stupefied spectators. Be it as it may, the economic fundamentals remained as shaky as ever, notwithstanding all spin-doctoring efforts deployed to make the facts look rosier. We commented that collapse might occur at any moment. We remain convinced that the house of cards should crumble even in the absence of the current coronavirus world catastrophe.

Facts are stubborn. The debt upward trend contrasts with the grossly flat trend of GDP (trends are shown by the linear regression lines in the chart). So much for the vain conceitedness of both socialist and rightist claims that each one is more capable than its rival to cure the country's financial ailments. Indeed, exception made of the odd lucky hit, for instance a propitious international economic context, current instances of left and right policies cannot and will not bear anything but identically lame results — right

and left

are just flavors to spice the basic process of milking the many to feed the few. The real stuff is and shall remain the same wasted effort to make a comatose system survive a few beats more.

The prime minister does his best to persuade on his country fellows that the economy made a turn-around, the finances got under control, hardship will soon be a thing of the past, and that a spectacular bonanza awaits the Portuguese around the corner. As the chart data points suggest, some solace resulted from the recent softening of the debt, coupled with the slight progress of GDP. But the healing is still out of sight, and the coronavirus pandemic is putting a brutal stop on such hollow promises.

Most of the assuagement has resulted from exogenous factors, inherently circumstantial and volatile. The over-sufficient supply of cheap money by the European Central Bank (ECB) allowing for lower interest rates on the debt has been a great help. The ECB, however, had announced that the liquidity tap should dry out soon. Interest rates were bound to bounce back to ponderous levels. The new flow of easy money promised by the ECB and the EU to cope with the adverse consequences of the pandemic will provide some breathing space. Again, it will only be a temporary fix.

The avalanche of tourists who deserted other destinations deemed riskier to pour into Portuguese hotel rooms, restaurant halls, and Bread-and-Breakfast lodgings, leaving a trail of fresh money behind, offered a big break, notwithstanding tourism becoming a scourge for locals who have to cope with the rise of prices, the scarcity of housing, the increasingly difficult access to needed services, and an overall deteriorating daily environment. However, further to data showing already a softening demand, the containment regulations imposed by the pandemic just killed tourism instantly.

The 2019 multiplication of sectoral protests and strikes — and the ensuing loss of work days — from dockers, nurses, health care providers, educators, railwaymen, judicial magistrates and personnel, firemen, truck drivers, civil servants down to police forces is a tell-tale symptom of the clumsiness of the government's economic contraption.

Despite their blustering, government executives can't but do more of the same. On the spending side, they pursue the aggressive pruning of government expenses, mainly in the social sector, thus lowering the level of service in health, education, justice, transportation, utilities, practically everywhere. The national budget becomes an exercise of make-believe following a well-known script. After some reasonable resistance, the administration yields to pressure by parliament groups and includes various budget items, for the sake of mollifying the opposition and obtaining the parliament vote. Thereafter, the government freezes the corresponding appropriations, postpones expenses sine die, and simply reneges its commitments. Spending is rubber-stamped only for selected areas. No restrictions for the hush-hush military missions in Afghanistan, Kosovo and Central Africa. Or to provide with juicy rents the owners of idle motorways and second-rate hospitals, or the developers of pointless bullet-trains. Or to finance futile projects expected to yield patronage opportunities to the political caste.

Elsewhere let it be chaos. Trains do not run for want of material or simply fall apart on the tracks. New pensioners are not paid, for lack of clerks to process their files. Surgeries are indefinitely postponed for shortage of medical teams. Oncology patients wait in the corridors because the wards remain closed. Maintenance of roads and bridges have to wait for better days. In the meantime the more decrepit ones collapse , leaving behind a trail of wrecked vehicles and drivers. Medical prescriptions cannot be issued because software systems are out of service. Schools become a purgatory for pupils, officials and teachers alike. Issuance of identity cards and other official papers is halted by failing software systems. And so on. A sure prescription for ruining the nation's strengths and to further plunge public and private agents in debt down the road.

On the income side, the government proceeds with the discount sale of the remainders of public assets, thus emptying the nation's treasure chest. It also resorts to stratagems such as selling residence permits and passports to wealthy and often shady foreigners, or offering a tax shelter to European pensioners — practices that leave a funny taste in the tongue if one considers how the political establishment indulges in patriotic and fiscal rectitude rhetoric. To conceal the harsh reality behind a smokescreen of pampering deceit, government manipulates the tax structure in a way to let the citizen believe that his disposable income remains untouched, only to strike him downstream with an orgy of benefit cuts, tax rate increases on consumption, and surcharges on consumption taxes.

This is easily proven. The Coelho government, against a background of economic recession, under the austerity diet agreed with the Troika, milked taxpayers with an individual tax scheme that grew at the pitiless annual average rate of 6.43%. The socialist Costa, advised by his Harvard-trained minister of finance, proved more astute. He reduced the pressure on the individual tax (to an average rate of 0.42%), while rising the VAT (value added tax) at the annual rate of 5.12% (against 2.58% for the Coelho mandate). The political interest is obvious. Costa can boast of decelerating taxation on individuals and increasing disposable income — both formally true —, while siphoning off more taxes from everybody, as VAT ascends to 23.48% of a growing (at 4.54% average) tax burden, while individual tax contributes a lower 17.52% to the tax burden, despite a progressing taxable GDP base.

But the bag of tricks quickly exhausts its potential. Government debt, instead of plunging, keeps climbing. In fact it just reached its two historical highests in May 2019 and again in February 2020, and remains stuck above the 120% of GDP mark. It is a bad omen for the commoner, condemned to further belt tightening, and to seek solace in private debt. For the resourceful ones, they may always resort to their customary deploy of cunning.

Although not inherently bad, government debt may be a curse under some circumstances. Similar in this specif respect to private debt, government debt may dissolve all by itself if inflation runs into high gear. Unfortunately for Portuguese finance's executives, inflation has been and will likely remain inconsequential for yet some time. Debt may also be a lesser evil if income (fiscal income generated by a swelling GDP) grows at a fast pace. However, if and when debt runs far ahead of GDP, the amount of work and wealth that the nation has to put aside to pay for interest on the debt becomes an overburden, diverting resources from other more advantageous uses: well-being, public health, education, infrastructure, social solidarity, innovation, employment, etc. In the case of Portugal, not only debt runs far ahead of GDP, but it also runs quite faster (the slope of the debt regression line is many fold steeper than that of GDP, for the period covered in the chart.) This simply means that a chunkier slice of wealth is being allocated to interest remuneration and loan payback, in pure waste of precious resources. Quite a dismal scenario. Government cash-flows will be hard pressed to sustain the current set-up for much longer.

Another issue is the usage made of the debt. The general rule should be to use debt to finance activity whose rate of return is greater than its cost, that is to say the interest rate to be paid to debt holders. In the case of Portugal, and in a context of low inflation, this has not been the case, with the result that the growing debt has been inducing nothing but further belt-tightening and overspread impoverishment.