areppim: information, pure and simple

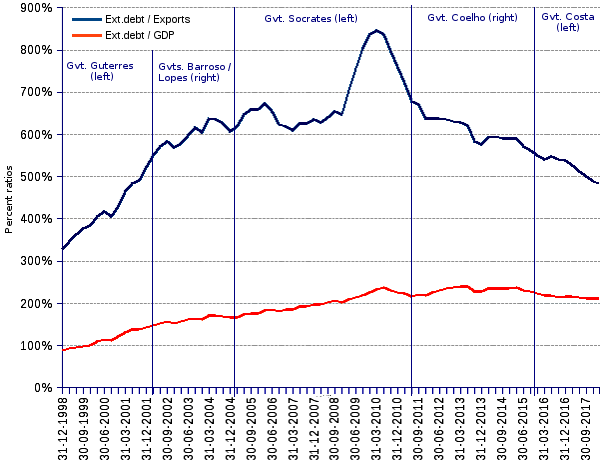

Portuguese external debt is quite a burden for an economy with the size, the structure, and the frailties of Portugal's. Amounting to twice the size of the country's GDP and almost five fold the value of yearly exports, it hangs over the country with a sense of foreboding.

Central government carries the heavier share of the external debt with 35%, followed by the Central bank at 27% and the private sector at 26%. In other words, both the state and the business sectors are indebted up to their noses, thus placing the country at the mercy of the foreign decision makers' whims. Debt is only a few steps away from insolvency, and insolvency often reduces debtors, either individuals or nations, to slavery.

Former Prime Minister Guterres, the socialist who is currently the United Nations Secretary General, had a deep impact on the debt, boosting it up to 150% of GDP and more than 550% of exports. The ride was merrily pursued by the right-wing Barroso and Lopes governments. After the ruinous rule of socialist Sócrates, during which foreign debt ascended to its record peak, both right-wing Coelho and socialist Costa succeeded in curbing the upward trend. This has been achieved mainly by improving the current account. By the end of 2012, the trade balance started to show a positive residual, after a very long string of negative results. In parallel, tourism income started to grow at a fast pace.

That is good news. However, the recovery rests upon a frail foundation. The salient contributors to the curve inflection are far from robust. Vehicle assembly lines account for 10% of exports but their headquarters, located in Germany and France, incessantly threaten to move their lines to more complacent locations if Portugal does not comply with their wishes. Mineral fuels including oil refining represent 6% of exports, but the business is dependent upon a volatile crude oil supply, and an unstable refined products demand. Likewise for electrical machinery and equipment (6%), and for plastics (5%). Furthermore, such industries as oil refineries or cellulose pulp plants incur a huge environmental cost which, sooner or later the country, not the buyers, will have to bear alone.

As for tourism, the recent surge is greatly due to the chaos caused by the wars engaged by the NATO powers in Central Asia, Middle East and Africa. Tourist flows have been deflected to safer destinations such as Portugal. However, it is not unreasonable to assume that the country' appeal may fade away as decidedly as it burgeoned. It may even become as unsafe as other dangerous destinations. After all, the presence of Portuguese military among the NATO forces in the Balkans, in the Middle East, in Central Asia and in Africa may be noticed by the kind of vindictive fellows that made some places in France and elsewhere quite hazardous locations to stroll around.

The fact remains that the road is currently less bumpy for Portugal. Can the country take advantage of the bonanza and improve the fundamental components of its vulnerable economy? Historically, Portugal has been blessed with cyclical inflows of wealth. The 16th century's spices from the East. The 18th century's gold and precious stones from Brazil. The 19th century's profits from the Atlantic slave trade. The late 20th century's pouring of European Union money. Regretfully, in all instances, the wealth was rapidly wasted, and the country relapsed in its deep slumbering. As yet, nothing suggests that the current situation will evolve otherwise.