areppim: information, pure and simple

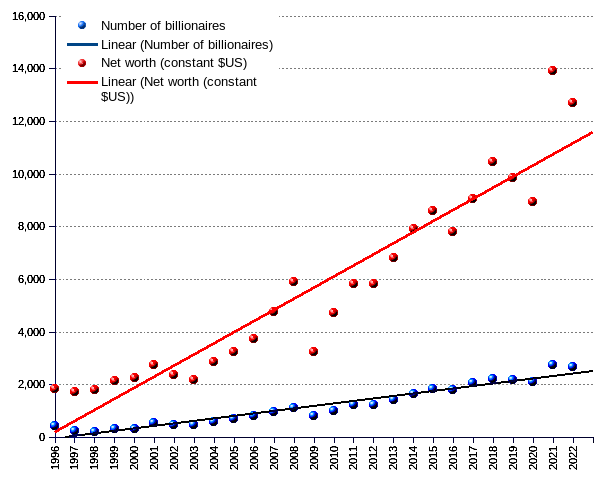

The share of wealth grabbed by the super-rich is staggering. From constant US$1.8 trillion in 1996, it climbed to 12.7 in 2022. Billionaires make just 0.000034 percent of the world population, but their current wealth is the equivalent of 12.8 percent of the GWP (gross world product). Nothing seems able to stop them. Their number has gone up, from 423 in 1996 to 2,668 in 2022 (average growth rate of 7.3% — against 1.2% for the world population). Their assets have grown with a similar unrelenting momentum (7.7% average annual growth, against 2.3% for GWP, both in constant dollars).

In plain terms, the ultra-rich captured a fast growing slice of the world’s wealth, while the good ordinary people struggle with increasing economic suffocation. The harsh winds of economic crises, while driving millions to the depths of destitution, seem to not affect the overall billionaires’ standings. Quite an amazing show.

We should ask ourselves whether such a chasm between the handful of ultra-rich and the vaster community of common people is irrelevant, or rather a symptom of a severe disease. The emergence of a ponderous and fast bulging entity is often a symptom of a serious disorder. In natural ecology, the presence of a thriving predator ruins the balance of the milieu and leads ultimately to the downfall of the predator itself. In physiology, cancers feature an abnormal growth of certain cells that spread to other parts of the body and unmercifully destroy the host organism. In astronomy, black holes can grow further by absorbing mass from its surroundings, including other stars, and evolve into super massive black holes. In urban sociology, the sprawling of a great city into a thickly populated megalopolis entails a dramatic deterioration of life conditions, the disruption of the ecological environment, massive immigration, and the eventual collapse of the social fabric. In human history, empires grow and expand territorially by successfully assailing and overpowering their neighbors, only to stretch their reach beyond their actual power to keep the variety of ethnic groups, geographies, factional interests, cultures, customs, and crafts under the same roof — thus faded the Persian, Roman, Muslim Caliphate, Mongol, Seljuk, Ottoman, British and a number of other once flourishing empires.

Growth must come to a stop at some point in time. An infant grows to a toddler, to a child, to an adolescent, to an adult. He may develop to become 2 meter tall, and 100 kg heavy. But nature sets limits that prevent him from ever being 5 meter tall or 500 kg heavy. Standard economists, nevertheless, are so engrossed with their linear arithmomania that they gleefully devise everlasting growth (and yet "sustainable", they claim) models, thus assuaging any concerns that the predators might have about the soundness of their insatiable greediness. As the rich get richer, they contend, the wealth trickles down to the gratified poor. In their minds, the discipline of economics is exempt from the laws that rule growth and change in the science realm.

Ancient Greek mythology contains an ominous warning against greed. Tantalus was extremely rich and favored by the gods, at which table he sat. His extravagant good luck made him behave eerily, committing many wrongdoings such as stealing ambrosia and nectar from the gods, demanding eternal life from Zeus, refusing to give back the gold dog claimed by Hermes, and, the worst of all, sacrificing his own son Pelops, cutting him into pieces, cooking him and serving him up in a banquet to ingratiate the gods. It was one offense too many. The infuriated Zeus sentenced him to suffer from unquenchable thirst and unappeasable hunger, with fruits hanging above his head and freshwater flowing under his chin but out of reach for all eternity. Temptation without satisfaction.

Today billionaires' behavior is as callous and relentless as the mythological creature's. They do not have any time for the armies of wage workers who toil to earn a living, and they loath the miserable good-for-nothing unemployed. Their exclusive concern is the value growth of their stock holdings. For this purpose, they pay mercenary executives to do the dirty work. The latter meekly pick in their toolbox whatever devices seem appropriate for the job.

They split work schedules, substituting precarious jobs, part-time assignments and moonlighting to regular and steady employment, however modest. They compress workers' remunerations to the subsistence level, while wrapping people in a haze of marketing-induced wants. Common people cannot afford to buy the goods? No problem, they design debt instruments that will provide the feeling of ownership at the price of unending slavery. Former slaves were costly: the master had to supply, not only the whip, but also some shelter and food. Modern slaves cost nothing, they do the enslaving all by themselves.

Contrary to the frustrated Tantalus, modern billionaires can have it all. They relish the rapture of stockpiling interests and capital gains. They enjoy the refinements of unique lifestyles. They indulge in the self-aggrandizing demonstrations of a generous heart. They can even "cook and devour their son Pelops", so to speak, in all impunity — earth resources are massively depleted and mountains of waste pile up to make them wealthier. And the gods, what the heck do they do? Well, they just look at the show with torpidness, they do not budge the little finger of their alleged invisible hand. Unlike Greek gods, modern ones are disinclined to mess with human affairs.

The 2008 global financial debacle prompted many rationalizations about the end of speculative finance, unruly capitalism, privatization of gains and nationalization of losses, and unbridled inequality. The old, wild financial capitalism seemed doomed. In 2021, thirteen years and another major crisis later (the 2019 pandemic), it reached new heights! Nothing seems to threaten its irresistible ascent. Until Zeus awakes from his peaceful slumber and decides that enough is enough.

| Year (Check detailed lists) |

Number | Net Worth | Average | Median ² | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| USD billion current | USD billion constant (2012=100) ¹ |

USD billion current | USD billion constant (2012=100) ¹ |

USD billion current | USD billion constant (2012=100) ¹ |

||

| 1996 | 423 | 1,049.5 | 1,825 | 2.5 | 4.3 | 1.9 | 3.0 |

| 1997 | 224 | 1,010.0 | 1,727 | 4.5 | 7.7 | 2.9 | 4.5 |

| 1998 | 209 | 1,069.1 | 1,807 | 5.1 | 8.6 | 3.3 | 5.0 |

| 1999 | 298 | 1,270.9 | 2,119 | 4.3 | 7.1 | 2.9 | 4.3 |

| 2000 | 322 | 1,386.1 | 2,260 | 4.3 | 7.0 | 2.9 | 4.3 |

| 2001 | 538 | 1,728.6 | 2,756 | 3.2 | 5.1 | 1.9 | 2.8 |

| 2002 | 472 | 1,515.5 | 2,379 | 3.2 | 5.0 | 1.8 | 2.6 |

| 2003 | 476 | 1,403.3 | 2,160 | 2.9 | 4.5 | 1.7 | 2.4 |

| 2004 | 587 | 1,917.2 | 2,874 | 3.3 | 4.9 | 1.9 | 2.6 |

| 2005 | 691 | 2,236.2 | 3,250 | 3.2 | 4.7 | 2.0 | 2.7 |

| 2006 | 793 | 2,645.5 | 3,730 | 3.3 | 4.7 | 2.0 | 2.6 |

| 2007 | 946 | 3,452.0 | 4,739 | 3.6 | 5.0 | 2.1 | 2.6 |

| 2008 | 1,125 | 4,381.0 | 5,902 | 3.9 | 5.2 | 2.2 | 2.7 |

| 2009 | 793 | 2,414.7 | 3,232 | 3.0 | 4.1 | 1.8 | 2.2 |

| 2010 | 1,011 | 3,567.8 | 4,719 | 3.5 | 4.7 | 3.5 | 4.2 |

| 2011 | 1,210 | 4,496.3 | 5,826 | 3.7 | 4.8 | 3.7 | 4.4 |

| 2012 | 1,226 | 4,574.5 | 5,818 | 3.7 | 4.7 | 2.1 | 2.4 |

| 2013 | 1,426 | 5,431.8 | 6,790 | 3.8 | 4.8 | 2.1 | 2.4 |

| 2014 | 1,645 | 6,446.5 | 7,910 | 3.9 | 4.8 | 2.2 | 2.5 |

| 2015 | 1,826 | 7,063.2 | 8,581 | 3.9 | 4.7 | 2.1 | 2.3 |

| 2016 | 1,810 | 6,482.6 | 7,798 | 3.6 | 4.3 | 2.1 | 2.2 |

| 2017 | 2,043 | 7,668.0 | 9,052 | 3.8 | 4.4 | 2.1 | 2.3 |

| 2018 | 2,208 | 9,059.6 | 10,443 | 4.1 | 4.7 | 2.2 | 2.3 |

| 2019 | 2,153 | 8,700.0 | 9,852 | 4.0 | 4.6 | 9.9 | 10.2 |

| 2020 | 2,095 | 8,000.0 | 8,943 | 3.8 | 4.3 | ||

| 2021 | 2,755 | 13,000.1 | 13,907 | 4.7 | 5.0 | 9.9 | 9.9 |

| 2022 | 2,668 | 12,700 | 12,700 | 4.8 | 4.8 | 8.46 | 8.46 |

| Average annual change rate | 7.3% | 10.1% | 7.7% | 0.4% | 4.1% | ||

| Average annual change rate 1996-2008 | 8.5% | 12.6% | 10.3% | 1.6% | -0.9% | ||

| Average annual change rate 2009-2022 | 9.8% | 13.6% | 11.1% | 1.2% | 11.1% | ||

| ¹ Adjusted by applying the $US GDP deflator. ² As from 2019, median values are computed for the top 500 billionaires only, by cause of unavailability of Forbes data. | |||||||

Source: Forbes List of billionaires. The World Bank-DataBank.