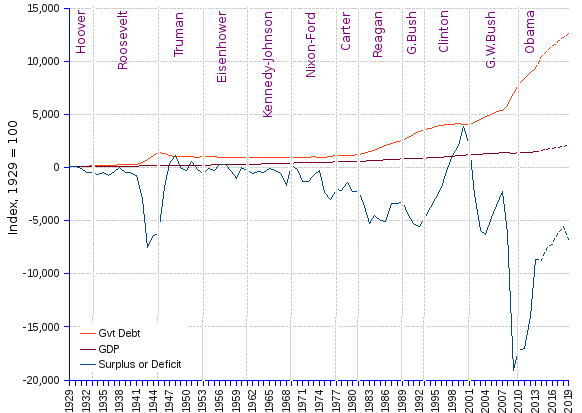

Federal budget deficits have been feeding government debt since the early 1980s. While GDP steadily grows from 1929 through 2013 at the average annual rate of 3.27% (doubling time 21.5 years), budget surpluses and deficits jump up and down, with increasingly deeper troughs, adding to a fast swelling government debt (average annual growth rate 5.55%, doubling time 12.8 years). Extending the analysis through 2019 by using the US budget estimates, GDP grows a bit faster, 3.41%, and the debt a bit slower, 5.53%. The gap between debt and GDP widens unflinchingly, self-feeding itself through further budget imbalances.

In the post-WWII era, the high-deficit trend was launched by Nixon, who also devised a canny subterfuge to overcome, at least partially, its undesired consequences. Struggling with the costs of the Vietnam war and with a negative current account, Nixon ran a string of high-deficit budgets, with the consequence of growing the public debt. Obviously, the dollar shrunk, putting heat on foreign dollar holders to convert their reserves into gold at a fixed exchange rate, in conformance with the Bretton Woods system. That would mean hell for the US, a strong enough reason for Nixon to cancel the direct convertibility of the USD to gold, and to let the dollar float freely in the foreign exchange market. Quite a magic trick to pay debt with funny money.

Credit must be given to President Carter's efforts to balance the budget, but this did not last long. The high-deficit trend gained momentum during Reagan's presidency. Exception made of Clinton's second mandate, during which the budget was balanced, thus allowing for a stabilization of the debt, the other presidencies have been extravagant spenders, the high end of prodigality being reached during G. W. Bush's mandates. The result is shown in the steep ascending line of government debt since 2001.

In the context of a spending behavior stronger than the economy growth, any attempt to restore a balanced budget can only be achieved by means of massive cuts on spending, or substantial tax increases, or a combination of both — assuming that other radical measures are excluded, such as repudiating the government debt, or drastically relinquishing state responsibilities.

An anemic economy, immersed in recession or sluggish growth as during the years since the 2008 financial meltdown, does not allow for tax raises to be very productive. High unemployment and compensation freezes hinder private incomes, and are not efficient tax feeders. Furthermore, on top of the social strain that high taxes place on the low-income strata of the population, they induce generalized consumption and investment restraint, thus causing still more foreclosures, more unemployment, lower incomes, lower tax revenues, and higher claims for government subsidies. The cure may prove worse than the evil.

The alternative is to accept budget deficits on a regular basis. Alas, if the occasional deficit is not a cause for alarm, continued deficits may inflate an already huge government debt. High debt in itself may not be too bad, provided debt is used to finance a thriving economy capable of generating fiscal revenue outweighing the debt burden. But it may become a many-sided evil if and when debt grows faster than the economy, or if interest rates are higher than the economy growth rate, if low inflation does not erode the real cost of debt-related expenses, or if the national currency does not depreciate fast enough.

Debt carries interest, and high debt not only causes an increase of net amounts of interest spending, but, other things remaining equal, it also tends to induce higher interest rates, thus feeding further budget deficits. In spite of a gross federal debt increase from 31.7% in 1981, at the beginning of Reagan's mandate, to 100.6% of GDP in 2013, net interest as percent of GDP has fallen significantly from 2.2% to 1.3% of GDP in the same period. The diverging trends are explained by the dramatic fall of the average interest rates: the US Daily Treasury Long Term Composite rate data gives 6.14% for 2000, and 3.41% for 2013 (beginning of the fiscal year). Declining interest rates succeeded in checking the adverse effects of the swelling debt. However, if low interest rates yield to higher rates, the impact on the budget can prove devastating.

A higher net interest burden implies the reduction of public sector savings, meaning less investment and slower growth of the capital stock. Furthermore, as government borrowing hits the "debt-limit" ceiling — de facto raised to $17.3 trillion following the debt-limit suspension of February 2014 —, the ability of the federal government to finance its activities is impaired, and its fiscal difficulties are exposed. Without enough money to pay the bills, any of its payments are at risk, including all government spending, mandatory payments, interest on debt, and payments to US bondholders. Whereas a government shutdown would be disruptive, a government default could be disastrous.

The problem is compounded by the long-term prospects. Indeed, even under the assumption that the economy will recover, thus stimulating consumption, investment, job creation and reinvigorated tax revenues, and also assuming that the government will put a stop to the expensive overseas military operations, accounting for a defense spending representing 3.8% of GDP in 2013, it still remains that the heaviest spending category, i.e. mandatory spending (e.g. Social Security, Medicare, unemployment insurance, deposit insurance, Medicaid, food stamps) amounted to 12.2% of GDP in 2013, and is forecast to grow to 13.5% of GDP in 2019.

Projections of the US age pyramid alert to an aging population. People above 65 years of age were 13% of the total 2010 population, and will be 19% in 2025. Spending with retirement and Medicare programs will follow suit. Conversely, working age population aged 20 to 64, will decrease from 60% in 2010 to 56% of the total population in 2025, thus bringing the number of working age people that provide for one old-age beneficiary (inverse dependency ratio) from 4.73 to 2.99. The net result will be that, assuming contribution and payment rates remain the same, outlays will inflate, while social insurance and retirement receipts (payroll taxes) will fall significantly.

The rapid growth of health care costs per capita will also inflate health-related government discretionary and mandatory spending (health programs, Medicare, Medicaid). The uncontrolled upwards trend of health care costs can be blamed to organic and management causes. On one hand, organic causes such as the longer life spans of individuals (the median age climbs from 36.7 years in 2010, to 38.9 years in 2015), as well as the ongoing progress of medical processes and technologies render health care services more lengthy, more widely available and more expensive for the government, the health insurers and the private pockets.

On the other hand, the management of the US medical system tends to make it inherently expensive, 40% to 100% more so than in other industrialized countries. A deficient health insurance coverage drives low-income patients to public hospital emergency services. Profit-oriented agents such as insurers and health maintenance organizations (HMO) dominate the health care industry pushing margins and prices up. Statutory constraints, such as the mandatory civil liability insurance for physicians, commanding outrageously priced premiums, or the government's exclusion in the negotiations of medical services and drug pricing are an obstacle to economies of scale in Medicare and Medicaid. Notwithstanding the government claims that the Affordable Care Act or "Obamacare" — the program that arose the opposition's furor leading to the government "shutdown" on 1st October 2013 — should reduce the growth in health care spending, government is taking such saving steps as putting a freeze on payment rates for physicians in order to obtain net reductions of Medicare costs, the total programmatic spending is estimated at 14% of GDP by 2019. No slack is contemplated for this spending item.

Fixing the federal fiscal problem will not be easy. Deficits will likely remain the rule, and debt will continue to pile up. There are however some good news for the US government. A little more than 37% of the government debt is external debt, of which 82% is labeled in USD. By just letting the Federal Reserve continue printing dollar bills, the Nixon's free-float gimmick causes the USD value to erode against the major currencies, thus lowering the US government liabilities towards foreign holders of US securities. Between 2003 and 2013 the USD lost 28% of its value (composite exchange rate, weighted by the total US securities held by each of European Union, China, Japan, United Kingdom and Switzerland). At this rate, the 2013 government outstanding debt would shrink by 8.4% in ten years. This is hardly a solution, because the same outstanding debt has increased by 439% between 2003 and 2013. It is also to be feared that US creditors, dissatisfied with the dollar decline, will repudiate the US currency as the dominant international payment currency, thus aggravating the US fiscal conundrum.

United States Federal Finance | ||||||

Year |

GDP |

Surplus or deficit (-) |

Government debt outstanding |

|||

| USD billion ¹ | Index, 1929=100 | USD billion ¹ | Index, 1929=100 | USD billion ¹ | Index, 1929=100 | |

| 1929 | 1,055.6 | 100.0 | 7,410.4 | 100.0 | 170.9 | 100.0 |

| 1930 | 965.8 | 91.5 | 7,733.4 | 104.4 | 169.6 | 99.2 |

| 1931 | 904.1 | 85.6 | -5,395.9 | -72.8 | 196.2 | 114.8 |

| 1932 | 787.5 | 74.6 | -36,182.0 | -488.3 | 257.8 | 150.8 |

| 1933 | 777.6 | 73.7 | -35,396.5 | -477.7 | 306.6 | 179.4 |

| 1934 | 861.4 | 81.6 | -46,235.2 | -623.9 | 348.8 | 204.1 |

| 1935 | 938.2 | 88.9 | -35,413.8 | -477.9 | 362.6 | 212.1 |

| 1936 | 1,059.6 | 100.4 | -53,746.3 | -725.3 | 421.8 | 246.8 |

| 1937 | 1,113.6 | 105.5 | -26,250.9 | -354.2 | 436.0 | 255.1 |

| 1938 | 1,076.7 | 102.0 | -1,096.6 | -14.8 | 457.9 | 267.9 |

| 1939 | 1,162.6 | 110.1 | -35,398.0 | -477.7 | 503.0 | 294.3 |

| 1940 | 1,265.0 | 119.8 | -35,881.1 | -484.2 | 528.0 | 308.9 |

| 1941 | 1,488.9 | 141.0 | -56,871.5 | -767.5 | 563.6 | 329.7 |

| 1942 | 1,770.3 | 167.7 | -218,652.0 | -2,950.6 | 772.3 | 451.8 |

| 1943 | 2,072.0 | 196.3 | -556,503.1 | -7,509.8 | 1,394.4 | 815.8 |

| 1944 | 2,237.5 | 212.0 | -473,864.1 | -6,394.6 | 2,002.8 | 1,171.7 |

| 1945 | 2,215.9 | 209.9 | -461,814.1 | -6,232.0 | 2,512.2 | 1,469.7 |

| 1946 | 1,959.0 | 185.6 | -137,036.7 | -1,849.2 | 2,316.8 | 1,355.4 |

| 1947 | 1,937.6 | 183.6 | 31,147.3 | 420.3 | 2,002.2 | 1,171.3 |

| 1948 | 2,018.0 | 191.2 | 86,620.6 | 1,168.9 | 1,852.6 | 1,083.8 |

| 1949 | 2,007.0 | 190.1 | 4,266.6 | 57.6 | 1,859.4 | 1,087.8 |

| 1950 | 2,181.9 | 206.7 | -22,668.8 | -305.9 | 1,870.5 | 1,094.3 |

| 1951 | 2,357.7 | 223.4 | 41,425.7 | 559.0 | 1,732.7 | 1,013.6 |

| 1952 | 2,453.7 | 232.4 | -10,136.1 | -136.8 | 1,729.0 | 1,011.5 |

| 1953 | 2,568.9 | 243.4 | -42,798.8 | -577.6 | 1,753.8 | 1,026.0 |

| 1954 | 2,554.4 | 242.0 | -7,536.1 | -101.7 | 1,771.4 | 1,036.3 |

| 1955 | 2,736.4 | 259.2 | -19,217.9 | -259.3 | 1,761.7 | 1,030.7 |

| 1956 | 2,794.7 | 264.7 | 24,506.4 | 330.7 | 1,693.5 | 990.7 |

| 1957 | 2,853.5 | 270.3 | 20,503.6 | 276.7 | 1,625.7 | 951.0 |

| 1958 | 2,832.6 | 268.3 | -16,271.0 | -219.6 | 1,623.8 | 950.0 |

| 1959 | 3,028.1 | 286.9 | -74,469.7 | -1,004.9 | 1,650.1 | 965.3 |

| 1960 | 3,105.8 | 294.2 | 1,720.7 | 23.2 | 1,636.8 | 957.6 |

| 1961 | 3,185.1 | 301.7 | -18,856.7 | -254.5 | 1,633.9 | 955.9 |

| 1962 | 3,379.9 | 320.2 | -39,915.1 | -538.6 | 1,665.6 | 974.4 |

| 1963 | 3,527.1 | 334.1 | -26,269.0 | -354.5 | 1,689.4 | 988.3 |

| 1964 | 3,730.5 | 353.4 | -32,176.5 | -434.2 | 1,695.7 | 992.0 |

| 1965 | 3,972.9 | 376.4 | -7,537.4 | -101.7 | 1,694.8 | 991.5 |

| 1966 | 4,234.9 | 401.2 | -19,214.4 | -259.3 | 1,662.2 | 972.4 |

| 1967 | 4,351.2 | 412.2 | -43,640.5 | -588.9 | 1,647.2 | 963.6 |

| 1968 | 4,564.7 | 432.4 | -121,862.7 | -1,644.5 | 1,683.4 | 984.8 |

| 1969 | 4,707.9 | 446.0 | 14,965.6 | 202.0 | 1,632.8 | 955.2 |

| 1970 | 4,717.7 | 446.9 | -12,462.2 | -168.2 | 1,626.5 | 951.5 |

| 1971 | 4,873.0 | 461.6 | -96,115.0 | -1,297.0 | 1,661.4 | 971.9 |

| 1972 | 5,128.8 | 485.9 | -93,473.3 | -1,261.4 | 1,708.7 | 999.6 |

| 1973 | 5,418.2 | 513.3 | -56,542.5 | -763.0 | 1,737.6 | 1,016.5 |

| 1974 | 5,390.2 | 510.6 | -21,351.0 | -288.1 | 1,653.3 | 967.2 |

| 1975 | 5,379.5 | 509.6 | -169,587.5 | -2,288.5 | 1,698.3 | 993.6 |

| 1976 | 5,669.3 | 537.1 | -222,627.5 | -3,004.3 | 1,873.3 | 1,095.9 |

| 1977 | 5,930.6 | 561.8 | -152,557.4 | -2,058.7 | 1,986.9 | 1,162.4 |

| 1978 | 6,260.4 | 593.1 | -157,227.1 | -2,121.7 | 2,049.6 | 1,199.1 |

| 1979 | 6,459.2 | 611.9 | -99,941.1 | -1,348.7 | 2,028.3 | 1,186.6 |

| 1980 | 6,443.4 | 610.4 | -166,190.2 | -2,242.7 | 2,043.2 | 1,195.3 |

| 1981 | 6,610.6 | 626.2 | -162,579.3 | -2,193.9 | 2,054.4 | 1,201.9 |

| 1982 | 6,484.3 | 614.3 | -248,084.8 | -3,347.8 | 2,213.8 | 1,295.1 |

| 1983 | 6,784.7 | 642.7 | -387,524.0 | -5,229.5 | 2,568.3 | 1,502.5 |

| 1984 | 7,277.2 | 689.4 | -333,844.2 | -4,505.1 | 2,831.6 | 1,656.6 |

| 1985 | 7,585.7 | 718.6 | -370,507.1 | -4,999.8 | 3,181.6 | 1,861.3 |

| 1986 | 7,852.1 | 743.9 | -378,437.5 | -5,106.8 | 3,635.6 | 2,126.9 |

| 1987 | 8,123.9 | 769.6 | -249,762.3 | -3,370.4 | 3,920.5 | 2,293.5 |

| 1988 | 8,465.4 | 802.0 | -250,093.5 | -3,374.9 | 4,194.1 | 2,453.6 |

| 1989 | 8,777.0 | 831.5 | -236,796.5 | -3,195.5 | 4,432.9 | 2,593.3 |

| 1990 | 8,945.4 | 847.4 | -330,669.5 | -4,462.2 | 4,837.0 | 2,829.8 |

| 1991 | 8,938.9 | 846.8 | -389,810.2 | -5,260.3 | 5,306.7 | 3,104.5 |

| 1992 | 9,256.7 | 876.9 | -410,963.4 | -5,545.8 | 5,753.7 | 3,366.0 |

| 1993 | 9,510.8 | 901.0 | -352,645.7 | -4,758.8 | 6,099.5 | 3,568.3 |

| 1994 | 9,894.7 | 937.4 | -275,077.5 | -3,712.0 | 6,353.1 | 3,716.7 |

| 1995 | 10,163.7 | 962.8 | -217,425.7 | -2,934.1 | 6,596.3 | 3,858.9 |

| 1996 | 10,549.5 | 999.4 | -139,915.1 | -1,888.1 | 6,804.6 | 3,980.8 |

| 1997 | 11,022.9 | 1,044.2 | -28,021.9 | -378.1 | 6,931.4 | 4,055.0 |

| 1998 | 11,513.4 | 1,090.7 | 87,745.7 | 1,184.1 | 7,000.1 | 4,095.2 |

| 1999 | 12,071.4 | 1,143.6 | 156,873.3 | 2,116.9 | 7,064.1 | 4,132.6 |

| 2000 | 12,565.2 | 1,190.3 | 288,482.3 | 3,892.9 | 6,928.9 | 4,053.6 |

| 2001 | 12,684.4 | 1,201.6 | 153,088.4 | 2,065.9 | 6,933.0 | 4,055.9 |

| 2002 | 12,909.7 | 1,223.0 | -185,479.8 | -2,503.0 | 7,322.7 | 4,283.9 |

| 2003 | 13,270.0 | 1,257.1 | -435,236.4 | -5,873.3 | 7,818.9 | 4,574.2 |

| 2004 | 13,774.0 | 1,304.9 | -463,051.4 | -6,248.7 | 8,278.8 | 4,843.2 |

| 2005 | 14,235.6 | 1,348.6 | -346,062.1 | -4,670.0 | 8,623.4 | 5,044.8 |

| 2006 | 14,615.2 | 1,384.5 | -261,744.6 | -3,532.1 | 8,971.9 | 5,248.7 |

| 2007 | 14,876.8 | 1,409.3 | -165,100.9 | -2,228.0 | 9,254.3 | 5,413.9 |

| 2008 | 14,833.6 | 1,405.2 | -462,083.3 | -6,235.6 | 10,101.9 | 5,909.8 |

| 2009 | 14,417.9 | 1,365.8 | -1,412,688.0 | -19,063.6 | 11,909.8 | 6,967.5 |

| 2010 | 14,779.4 | 1,400.1 | -1,278,885.7 | -17,258.0 | 13,399.4 | 7,838.9 |

| 2011 | 15,052.4 | 1,426.0 | -1,259,307.7 | -16,993.8 | 14,331.9 | 8,384.4 |

| 2012 | 15,470.7 | 1,465.6 | -1,035,183.1 | -13,969.3 | 15,300.9 | 8,951.3 |

| 2013 | 15,761.3 | 1,493.1 | -637,503.3 | -8,602.8 | 15,971.1 | 9,343.4 |

| 2014 ² | 17,332.3 | 1,641.9 | -648,805.0 | -8,755.3 | 17,892.6 | 10,467.5 |

| 2015 ² | 18,219.4 | 1,726.0 | -563,564.0 | -7,605.0 | 18,713.5 | 10,947.7 |

| 2016 ² | 19,180.6 | 1,817.0 | -531,126.0 | -7,167.3 | 19,511.6 | 11,414.7 |

| 2017 ² | 20,199.4 | 1,913.5 | -457,827.0 | -6,178.2 | 20,261.7 | 11,853.5 |

| 2018 ² | 21,216.3 | 2,009.9 | -413,289.0 | -5,577.1 | 20,961.1 | 12,262.6 |

| 2019 ² | 22,196.1 | 2,102.7 | -502,672.0 | -6,783.3 | 21,670.7 | 12,677.8 |

| Average annual change rate (1929-2013) | 3.27 % | 5.55 % | ||||

| Doubling time in years (1929-2013) | 21.5 | 12.8 | ||||

| Average annual change rate (1929-2019) | 3.41 % | 5.53 % | ||||

| Doubling time in years (1929-2019) | 20.7 | 12.9 | ||||

| ¹ Constant dollars 2009=100, after applying the US GDP deflator. ² Estimates, 2015 Budget of the US Government. | ||||||

Sources: US Government Printing Office, US Treasury, US Bureau of Economic Analysis, US Census Bureau, Federal Reserve Board.