![]() Unemployment: Trends 1998-2013 | Zero unemployment model |

Unemployment: Trends 1998-2013 | Zero unemployment model |

Unemployment is generally viewed as one of today's biggest and unsolved problems, threatening both the economy recovery, and an already threadbare social restraint. According to ILO (International Labour Organization), the crowds of unemployed reached 201.8 million in 2013, not including at least 25 million "discouraged job seekers" — for comparison, consider that the total United States labor force counts 155 million. ILO's econometric projections forecast an ongoing swelling to attain 215 million by 2018, all attempts by numerous political leaders to boost employment notwithstanding.

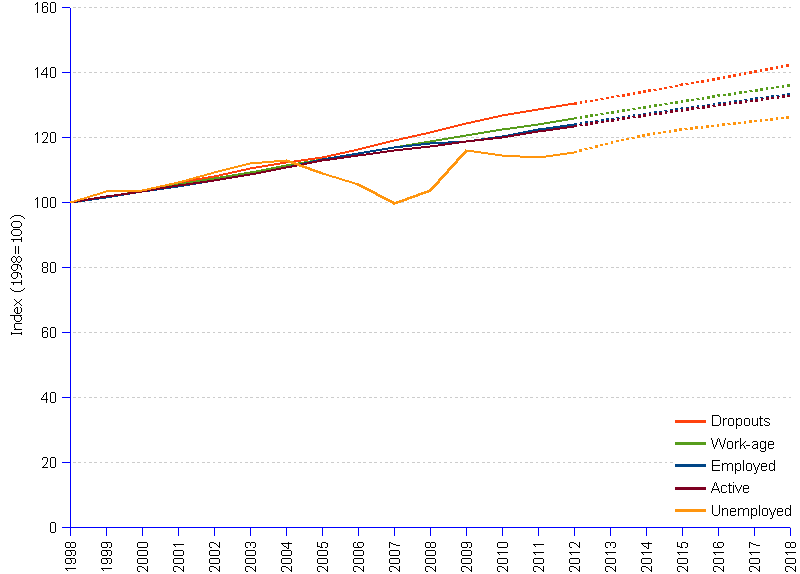

The unemployment reality portrayed in the chart (all values as indexes, 1998=100, to allow for easier trend comparisons) is certainly a much harder nut to crack than most professional soothsayers pretend to believe. Indeed, the data tell us a damning story: unemployment is there to last, the struggle for jobs is bound to become a daily worry for a growing portion of mankind, and neither the deflationary policies promoted by most governments under the ideological guidance of such wizards as the IMF (International Monetary Fund), the WB (World Bank), and the OECD (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development), nor the array of aggressive economic boosting measures advocated by their neo-keynesian adversaries seem capable of derailing the runaway unemployment phenomenon.

The way employed and unemployed, working-age and active populations fared in the last 20 years and are projected to develop in the coming future, suggests that decision-makers and their advisers who undertook the agenda of fighting unemployment, in fact (A) achieved its opposite; (B) could never do it; and anyway (C) aren't willing to do it.

Global Unemployment, Working-age and Active populations | ||||||||||

Year |

Working-age population ¹ |

Dropouts ² |

Active population ³ |

Unemployed⁴ |

Employed ⁵ |

|||||

| million | index | million | index | million | index | million | index | million | index | |

| 1998 | 4,103 | 100 | 1,420 | 100 | 2,683 | 100 | 170 | 100 | 2,513 | 100 |

| 1999 | 4,177 | 102 | 1,442 | 102 | 2,735 | 102 | 177 | 104 | 2,558 | 102 |

| 2000 | 4,255 | 104 | 1,477 | 104 | 2,778 | 104 | 177 | 104 | 2,601 | 104 |

| 2001 | 4,330 | 106 | 1,507 | 106 | 2,823 | 105 | 181 | 106 | 2,642 | 105 |

| 2002 | 4,409 | 107 | 1,538 | 108 | 2,871 | 107 | 186 | 109 | 2,685 | 107 |

| 2003 | 4,490 | 109 | 1,569 | 110 | 2,921 | 109 | 191 | 112 | 2,731 | 109 |

| 2004 | 4,571 | 111 | 1,595 | 112 | 2,976 | 111 | 193 | 113 | 2,784 | 111 |

| 2005 | 4,651 | 113 | 1,620 | 114 | 3,032 | 113 | 186 | 109 | 2,846 | 113 |

| 2006 | 4,728 | 115 | 1,656 | 117 | 3,073 | 115 | 180 | 106 | 2,893 | 115 |

| 2007 | 4,804 | 117 | 1,691 | 119 | 3,113 | 116 | 170 | 100 | 2,943 | 117 |

| 2008 | 4,879 | 119 | 1,728 | 122 | 3,151 | 117 | 177 | 104 | 2,974 | 118 |

| 2009 | 4,953 | 121 | 1,766 | 124 | 3,187 | 119 | 198 | 116 | 2,989 | 119 |

| 2010 | 5,028 | 123 | 1,803 | 127 | 3,225 | 120 | 195 | 115 | 3,030 | 121 |

| 2011 | 5,099 | 124 | 1,828 | 129 | 3,271 | 122 | 194 | 114 | 3,077 | 122 |

| 2012 | 5,171 | 126 | 1,854 | 131 | 3,317 | 124 | 197 | 116 | 3,120 | 124 |

| 2013 | 5,243 | 128 | 1,881 | 132 | 3,362 | 125 | 202 | 118 | 3,160 | 126 |

| 2014 | 5,314 | 130 | 1,908 | 134 | 3,406 | 127 | 206 | 121 | 3,200 | 127 |

| 2015 | 5,385 | 131 | 1,936 | 136 | 3,449 | 129 | 209 | 123 | 3,240 | 129 |

| 2016 | 5,453 | 133 | 1,964 | 138 | 3,489 | 130 | 211 | 124 | 3,278 | 130 |

| 2017 | 5,522 | 135 | 1,993 | 140 | 3,529 | 132 | 213 | 125 | 3,316 | 132 |

| 2018 | 5,590 | 136 | 2,022 | 142 | 3,567 | 133 | 215 | 126 | 3,352 | 133 |

| Average annual change 1998-2018 | 1.56% | 1.78% | 1.43% | 1.18% | 1.45% | |||||

| Average annual change 1998-2006 | 1.79% | 1.94% | 1.71% | 0.68% | 1.78% | |||||

| Average annual change 2007-2013 | 1.47% | 1.78% | 1.29% | 2.90% | 1.19% | |||||

| ¹ Working-age population is the population above a certain age. The ILO standard for the lower age limit is 15 years. ² Dropouts equal working-age population less active population, and are those working-age persons who are neither employed nor unemployed. ³ Active population equals the sum of the employed and the unemployed. ⁴ Unemployed include all persons of working age that during a reference period are without work, are available to start working, and took active steps to seek work. ⁵ Employed persons equal active population less unemployed. | ||||||||||

![]() Unemployment: Trends 1998-2013 | Zero unemployment model |

Unemployment: Trends 1998-2013 | Zero unemployment model |

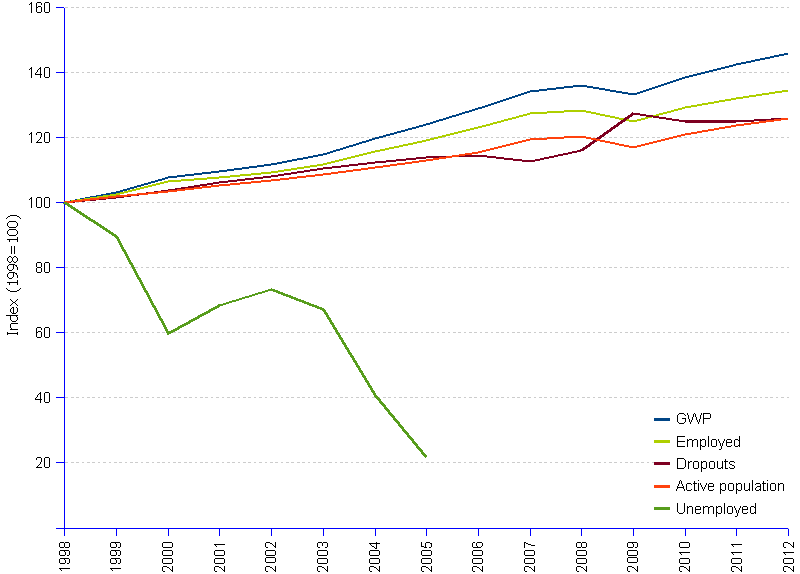

The reduction of the working hours schedule pegged to the productivity gains seems to be the only workable way to overcome the unemployment concern. The chart (index numbers, 1998=100, to allow for easier comparisons) illustrates the effects of the shortened schedule scenario applied retrospectively from 1998 through 2012, the corresponding data appearing in the table of the simplified model. The more salient features are the fast growth of employment, attached to GWP (gross world product) growth, the slowing down of working-age-neither-employed-nor-unemployed or "dropouts" growth, and the consequent undoing of unemployment, which evaporates by 2006.

The simplified model takes as given two variables: the working-age population numbers, and the GWP values. In the 15 years between 1998 and 2012, real GWP, that is adjusted to inflation for 2005=100, grew by US$ 17.2 trillion. This has been achieved by a parallel increase of the employed population of 607 million. It is easy to determine that the gross productivity per employed person grew at the average annual rate of 1.16%.

Other things remaining equal, namely the pay levels unchanged except for the deflation factor and the gross economic output as given, let us assume that the productivity gains are cut in halves: one half to further compensate investors, the second half to improve the labor status by shortening the work schedules, thus inducing the hiring of a larger portion of the active population. The results are a fast acceleration of employment that will siphon resources from the pool of active population, a rapid decrease of unemployment, and the resulting need to hire labor from the working-age-neither-employed-nor-unemployed pot. The unemployment problem would be fixed. In fact, by focusing human ingenuity on environment-friendly efficiency and productivity gains, instead of sheer product growth, a lasting sharing of work by all working-age persons, as well as a longer life span for planet earth could be achieved.

Obviously, labor is not a commodity that can be moved, reassigned, or re-skilled instantaneously. Some level of technical unemployment will always withstand — elapsed time to select, hire, induce, retrain and bring up to speed of workers, time between two jobs, time to change over production setups, etc. However, the model is just a sketch delineating an alternative and viable approach to the labor conundrum. It shows that it is possible in principle to eradicate the unemployment leprosy, to offer workers and their families better work and life conditions, to protect their income levels, all this without overheating the economy, thus gaining time to explore more environment-friendly living and working practices.

Of the extra US$ 17.2 trillion GWP generated between 1998 and 2012, a big chunk, exactly US$ 2.8 trillion or 16.2%, have been diverted to the balance sheets of the billionaires — a small club of 209 names in 1998 that grew to 1,153 in 2012. It is predictable that neither them, nor the vaster crowds of multimillionaires, nor even their high-paid surrogate agents — politicians, lobbyists, professional advisers, influencers, technicians — will look on calm and impassively while someone dares to take away a full half of their gargantuan cut. Fortunately for them, the discussion of the subject itself has been diligently inhibited on all sorts of pretenses. As for the underdogs, they ultimately face a simple choice: to demand instead of asking, to force the door and impose the debate, or to buy enough facial tissue to wipe the tears.

Zero Unemployment | ||||||||||

Year |

Gross World Product ¹ |

Active population ² |

Employed ³ |

Unemployed ⁴ |

Dropouts ⁵ |

|||||

| million | index | million | index | million | index | million | index | million | index | |

| 1998 | 37,327,740 | 100 | 2,683 | 100 | 2,513 | 100 | 170 | 100 | 1,420 | 100 |

| 1999 | 38,580,212 | 103 | 2,735 | 102 | 2,582 | 103 | 153 | 90 | 1,442 | 102 |

| 2000 | 40,217,907 | 108 | 2,778 | 104 | 2,676 | 107 | 102 | 60 | 1,477 | 104 |

| 2001 | 40,911,183 | 110 | 2,823 | 105 | 2,706 | 108 | 117 | 68 | 1,507 | 106 |

| 2002 | 41,755,075 | 112 | 2,871 | 107 | 2,746 | 109 | 125 | 73 | 1,538 | 108 |

| 2003 | 42,924,637 | 115 | 2,921 | 109 | 2,807 | 112 | 115 | 67 | 1,569 | 110 |

| 2004 | 44,714,096 | 120 | 2,976 | 111 | 2,907 | 116 | 69 | 41 | 1,595 | 112 |

| 2005 | 46,328,509 | 124 | 3,032 | 113 | 2,995 | 119 | 37 | 22 | 1,620 | 114 |

| 2006 | 48,218,630 | 129 | 3,099 | 116 | 3,099 | 123 | 1,629 | 115 | ||

| 2007 | 50,126,644 | 134 | 3,203 | 119 | 3,203 | 127 | 1,601 | 113 | ||

| 2008 | 50,848,135 | 136 | 3,230 | 120 | 3,230 | 129 | 1,649 | 116 | ||

| 2009 | 49,775,258 | 133 | 3,144 | 117 | 3,144 | 125 | 1,810 | 127 | ||

| 2010 | 51,770,602 | 139 | 3,251 | 121 | 3,251 | 129 | 1,777 | 125 | ||

| 2011 | 53,236,186 | 143 | 3,324 | 124 | 3,324 | 132 | 1,775 | 125 | ||

| 2012 | 54,483,213 | 146 | 3,382 | 126 | 3,382 | 135 | 1,789 | 126 | ||

| 2012: variation of model to actuals | 0 | +65 | +262 | -197 | -65 | |||||

| ¹ Real GWP (Gross World Product) in constant US dollars, 2005=100. | ||||||||||

| ² Total number of employed and unemployed persons, after modelization. For actual data see table of trends 1998-2013. | ||||||||||

| ³ To estimate the number of employed persons, (1) we computed the gross productivity per worker by dividing GWP by the actual employed persons; (2) we found that gross productivity increased at the average annual rate of 1.16%; (3) we allocated half of the productivity gains, the equivalent to an annual growth rate of 0.58%, to the workforce, sharing the workload among more workers. In 2012, this operation would have required an additional 262 million workers. | ||||||||||

| ⁴ Unemployed persons would have found jobs already by mid-2006, thus reducing unemployment to zero — technically an impossibility, ignored in this simplified exercise. | ||||||||||

| ⁵ In 2012, the hiring of 262 million workers more, would have required that 65 million former "Dropouts", e.g. senior workers and left-outs, join the labor force and contribute to deliver the GWP output. | ||||||||||

Sources: ILO - International Labour Organization, ILOSTAT Database, United Nations Population Division, and World DataBank – The World Bank