![]() Unemployment by gender | age |

Unemployment by gender | age |

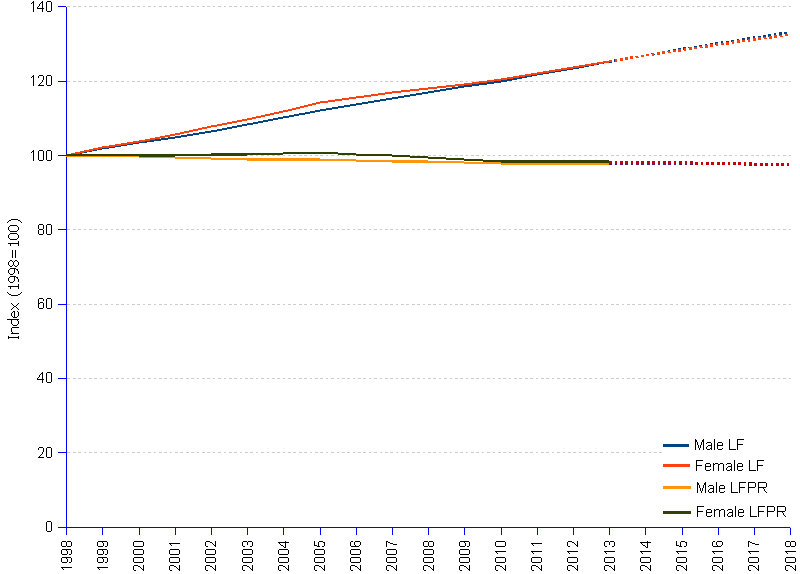

Total LFPR (labor force participation rate) has been declining regularly since 1998, moving from 65.4% of the total working-age population in 1998 to 64.1% in 2013. In practical terms, this means that 1.88 billion or 36% of working-age persons were, in 2013, out of the labor force, neither employed nor unemployed. ILO (International Labor Organization) anticipates further decreases bringing LFPR to 63.8% in 2018 (LFPR and working-age population appear in the chart as indexes, for 1998 = 100). A declining LFPR against the background of a growing working-age population sends an unequivocal sign that hard times for employment applicants are lurking on the horizon.

These trends should come as a surprise, considering that, from 1998 to 2013, working age population grew by 1,139.5 million persons, who should have joined under normal conditions the active population. Regretfully, only 679.1 million or 60% rallied the labor force, sending a vast crowd of 460 million people to the limbo where wander those that are neither working nor appearing in the unemployed records. How did they evaporate? A fraction of the entrants into the 65+ age group became pensioners, neither employed nor unemployed — but their number is of little significance since pension systems are not universal, and the growth of that age class between 1998 and 2013 has been of only 39.2 million. Technically, it is also possible that a handful may have earned access to the 1,342-strong club of world billionaires, a class of individuals typically known for being neither employed nor unemployed. Possible, but highly improbable — more likely the unaccounted for 460, minus 10 or 15 million persons vanished in the lower depths, augmenting the ranks of the wretched of the earth.

The analysis by gender shows a decrease of the female participation rate from 52% to 51.1%, as well as the parallel decrease of the male participation rate, from 78.8% to 77.2%. In percentage terms, both male LFPR and female LFPR fell from 1998 to 2013 at the same rate as the total LFPR, that is -0.1% per year. One could say that gender equality has been achieved in this respect: all three variables — male, female and total LFPR — have been falling at the same speed. But that is far from being good news, on the contrary it is ominous. The real meaning of the long-term trend is that, while the precariousness of both male and female working-age persons has been growing, the gender gap remains unaltered.

The core issue is that the number of people engaged in the labor market, whether employed or unemployed, is losing ground relative to the steadily increasing total working-age population. The untapped reserve of labor is growing much faster than employment opportunities. Female participation in the labor force increased slightly until 2005, suggesting a faster ingress of females in the labor market, thus narrowing the gender gap in the labor force structure, and allowing households to complement their incomes. It has been a short bonanza. As from 2006, and the 2007 financial crisis helping, female LFPR went downwards until 2013, almost three times faster than male LFPR. Meanwhile, male participation has been falling all along the period, somewhat faster until 2005, maybe to give room for females, and slower thereafter, as more females were dropped out. As from 2010, trends became similar for both genders, as respects the growth of the labor force, and the evolution of the labor participation rate. Nowadays, facing a situation of stalling workers' incomes, growing working-age population, and decreasing male and female participation rates, it is easy to forecast that gender equality becomes a more remote target, employment turns into an elusive mirage, and the average household income will continue to shrink away.

Labor Force Participation Rate by Gender | |||||||||

Year |

Global working-age Population ¹ |

Labor Force (Active Population) [LF] |

Labor Force Participation Rate [LFPR] |

||||||

Male | Female | Total |

Male | Female | Total |

Male | Female | Total |

|

| 1998 | 2,048 | 2,055 | 4,103 | 1,614 | 1,069 | 2,683 | 78.8% | 52.0% | 65.4% |

| 1999 | 2,085 | 2,093 | 4,177 | 1,644 | 1,091 | 2,735 | 78.8% | 52.1% | 65.5% |

| 2000 | 2,123 | 2,131 | 4,255 | 1,669 | 1,109 | 2,778 | 78.6% | 52.0% | 65.3% |

| 2001 | 2,161 | 2,169 | 4,330 | 1,694 | 1,129 | 2,823 | 78.4% | 52.0% | 65.2% |

| 2002 | 2,201 | 2,208 | 4,409 | 1,720 | 1,151 | 2,871 | 78.2% | 52.1% | 65.1% |

| 2003 | 2,241 | 2,249 | 4,490 | 1,749 | 1,173 | 2,921 | 78.0% | 52.1% | 65.1% |

| 2004 | 2,282 | 2,289 | 4,571 | 1,780 | 1,196 | 2,976 | 78.0% | 52.3% | 65.1% |

| 2005 | 2,322 | 2,329 | 4,651 | 1,811 | 1,220 | 3,032 | 78.0% | 52.4% | 65.2% |

| 2006 | 2,361 | 2,367 | 4,728 | 1,837 | 1,235 | 3,073 | 77.8% | 52.2% | 65.0% |

| 2007 | 2,399 | 2,405 | 4,804 | 1,863 | 1,250 | 3,113 | 77.7% | 52.0% | 64.8% |

| 2008 | 2,437 | 2,442 | 4,879 | 1,889 | 1,262 | 3,151 | 77.5% | 51.7% | 64.6% |

| 2009 | 2,474 | 2,479 | 4,953 | 1,913 | 1,274 | 3,187 | 77.3% | 51.4% | 64.3% |

| 2010 | 2,512 | 2,516 | 5,028 | 1,938 | 1,287 | 3,225 | 77.2% | 51.2% | 64.1% |

| 2011 | 2,548 | 2,551 | 5,099 | 1,966 | 1,305 | 3,271 | 77.2% | 51.2% | 64.2% |

| 2012 | 2,584 | 2,587 | 5,171 | 1,994 | 1,323 | 3,317 | 77.2% | 51.1% | 64.1% |

| 2013 | 2,620 | 2,622 | 5,242 | 2,022 | 1,340 | 3,362 | 77.2% | 51.1% | 64.1% |

| 2014 | 2,656 | 2,657 | 5,314 | 2,050 | 1,356 | 3,406 | 77.2% | 51.0% | 64.1% |

| 2015 | 2,692 | 2,692 | 5,385 | 2,076 | 1,373 | 3,449 | 77.1% | 51.0% | 64.1% |

| 2016 | 2,727 | 2,726 | 5,453 | 2,102 | 1,388 | 3,489 | 77.1% | 50.9% | 64.0% |

| 2017 | 2,761 | 2,760 | 5,522 | 2,126 | 1,403 | 3,529 | 77.0% | 50.8% | 63.9% |

| 2018 | 2,796 | 2,794 | 5,590 | 2,150 | 1,417 | 3,567 | 76.9% | 50.7% | 63.8% |

| Average annual change 1998-2018 | 1.6% | 1.5% | 1.6% | 1.4% | 1.4% | 1.4% | -0.1% | -0.1% | -0.1% |

| ¹ Total population aged 15+ | |||||||||

![]() Unemployment by gender | age |

Unemployment by gender | age |

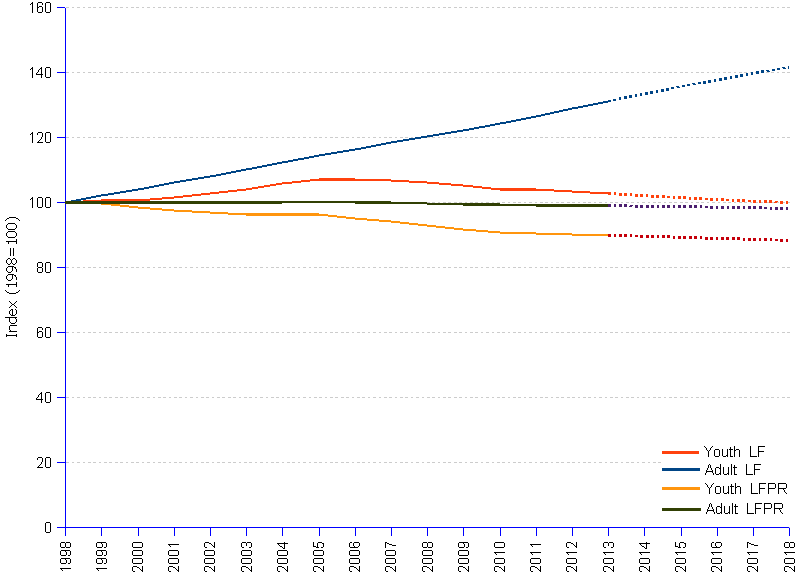

The labor market outlook for young people worsened in nearly every region of the world. Global youth employment is going through a gloomy phase: there were 37.1 million fewer young people in employment in 2013 than in 2007, while the global youth grew by 9.1 million over the same period. The future looks bleak. Global youth LFPR (labor force participation rate), at 48.5% in 2013 remains almost 3 percentage points below the pre-crisis level (LFPR and working-age population appear in the chart as indexes, for 1998 = 100).

Such a declining LFPR signals that a growing number of working-age young persons, totalling 620 million or 52% of working-age youth in 2013, drop out of the labor force, whatever the reasons. The youth LFPR had been falling since 1998, but the phenomenon accelerated with the 2007 world crisis. More young people, frustrated with their employment prospects, desert the labor market. Youth labor force has decreased by 22 million from 2007 to 2013. While adult labor force, comprising increasing numbers of unemployed, grew steadily during the period under review, youth labor force stalled with the crisis, and took a downward path thereafter, going from an annual average growth rate of 0.9% till 2006, to a negative rate of -0.6% from 2007 to 2013. ILO anticipates this trend to continue through 2018. Which is equivalent to forecasting an inflating army of idle youth, not enrolled in the labor market.

According to ILO, more young people are choosing to stay longer in education, thus postponing the transition from school to the labor market. They may be listening to, and believing far too much in reports that promote the benefits of schooling on the basis of biased research performed in privileged environments. Longer schooling is not likely the most effective way to win the credits required to lift a job. ILO research suggests indeed that difficulties in transition from school to work are associated not only with the lack of work experience, but also with large mismatches between skills possessed by young people and skills demanded by employers. Many young people are drawing a similar lesson from their daily experience, realizing that their schooling fails to unlock any door whatsoever, and that they are condemned to remain outside the railings of the labor market, maybe forever. That is why an increasing number of young people are fueling the proportion of NEET (not in employment, education or training).

The relationship between school and the job needs plenty of fresh thinking. In the 1960s, Ivan Illich provocatively promoted the idea of deschooling society. He claimed that most of what one knows is learned outside the school walls — indeed one hardly learns anything valuable at school. The real purpose of schools, he stated defiantly, is to keep kids out of the streets. And he advocated the idea of a personal entitlement to a lifelong credit to education or training to be used by the concerned individual in function of the personal needs and personal readiness. As we all know, today's prevailing approach is at odds with such ideas, and has instead implemented a "more of the same" policy for the masses: more years at school, more educational paths, more curricula, more specializations, more items in the schooling menu, all of them conducive to nil employment.

Although school is still genuinely managed as a youth control tool, it does not prevent kids from haunting the streets — in fact more and older kids are spending more time doing weird things out there. Masses of skeptical youth do not expect to learn anything useful from teachers that are helpless to grasp their attention or excite their curiosity, in schools that are the reflection itself of the society's incompetence to offer any meaningful prospects to the majority. Acknowledging these changes, rulers chose to rely on ubiquitous (and useless, as research shows) video-surveillance, and on more aggressive and intrusive law-and-order instruments, rather than on schools to try and control those that are left out of full social life. One feels hard pressed to understand how such costly policies will revert the trend, open job opportunities, and recruit more youth to actively participate in the labor force.

Labor Force Participation Rate by Age Group | |||||||||

Year |

Global working-age Population ¹ |

Labor Force (Active Population) [LF] |

Labor Force Participation Rate [LFPR] |

||||||

Youth | Adult | Total |

Youth | Adult | Total |

Youth | Adult | Total |

|

| 1998 | 1,054 | 3,049 | 4,103 | 567.2 | 2,116 | 2,683 | 53.8% | 69.4% | 65.4% |

| 1999 | 1,066 | 3,112 | 4,177 | 571.9 | 2,163 | 2,735 | 53.7% | 69.5% | 65.5% |

| 2000 | 1,080 | 3,174 | 4,255 | 572.4 | 2,206 | 2,778 | 53.0% | 69.5% | 65.3% |

| 2001 | 1,097 | 3,234 | 4,330 | 576.3 | 2,247 | 2,823 | 52.6% | 69.5% | 65.2% |

| 2002 | 1,116 | 3,293 | 4,409 | 583.1 | 2,288 | 2,871 | 52.3% | 69.5% | 65.1% |

| 2003 | 1,136 | 3,354 | 4,490 | 590.5 | 2,331 | 2,921 | 52.0% | 69.5% | 65.1% |

| 2004 | 1,155 | 3,416 | 4,571 | 600.3 | 2,376 | 2,976 | 52.0% | 69.6% | 65.1% |

| 2005 | 1,172 | 3,479 | 4,651 | 608.3 | 2,423 | 3,032 | 51.9% | 69.6% | 65.2% |

| 2006 | 1,185 | 3,543 | 4,728 | 608.0 | 2,464 | 3,073 | 51.3% | 69.6% | 65.0% |

| 2007 | 1,195 | 3,609 | 4,804 | 605.8 | 2,507 | 3,113 | 50.7% | 69.5% | 64.8% |

| 2008 | 1,202 | 3,677 | 4,879 | 602.4 | 2,549 | 3,151 | 50.1% | 69.3% | 64.6% |

| 2009 | 1,207 | 3,747 | 4,953 | 597.0 | 2,590 | 3,187 | 49.5% | 69.1% | 64.3% |

| 2010 | 1,209 | 3,818 | 5,028 | 590.8 | 2,634 | 3,225 | 48.9% | 69.0% | 64.1% |

| 2011 | 1,209 | 3,890 | 5,099 | 590.1 | 2,681 | 3,271 | 48.8% | 68.9% | 64.2% |

| 2012 | 1,207 | 3,964 | 5,171 | 587.5 | 2,729 | 3,317 | 48.7% | 68.9% | 64.1% |

| 2013 | 1,204 | 4,039 | 5,242 | 583.8 | 2,778 | 3,362 | 48.5% | 68.8% | 64.1% |

| 2014 | 1,200 | 4,113 | 5,314 | 579.9 | 2,826 | 3,406 | 48.3% | 68.7% | 64.1% |

| 2015 | 1,197 | 4,187 | 5,385 | 576.4 | 2,873 | 3,449 | 48.1% | 68.6% | 64.1% |

| 2016 | 1,195 | 4,258 | 5,453 | 573.1 | 2,916 | 3,489 | 48.0% | 68.5% | 64.0% |

| 2017 | 1,193 | 4,328 | 5,522 | 570.4 | 2,959 | 3,529 | 47.8% | 68.4% | 63.9% |

| 2018 | 1,193 | 4,397 | 5,590 | 568.1 | 2,999 | 3,567 | 47.6% | 68.2% | 63.8% |

| Average annual change 1998-2018 | 0.6% | 1.8% | 1.6% | 0.01% | 1.8% | 1.4% | -0.6% | -0.1% | -0.1% |

| Average annual change 1998-2006 | 1.5% | 1.9% | 1.8% | 0.9% | 1.9% | 1.7% | -0.6% | 0.03% | -0.1% |

| Average annual change 2007-2013 | 0.1% | 1.9% | 1.5% | -0.6% | 1.7% | 1.3% | -0.7% | -0.2% | -0.2% |

| ¹ Total population aged 15+ | |||||||||

Sources: ILO - International Labor Organization, Harmonised datasets (1990-2020), ILOSTAT Database.