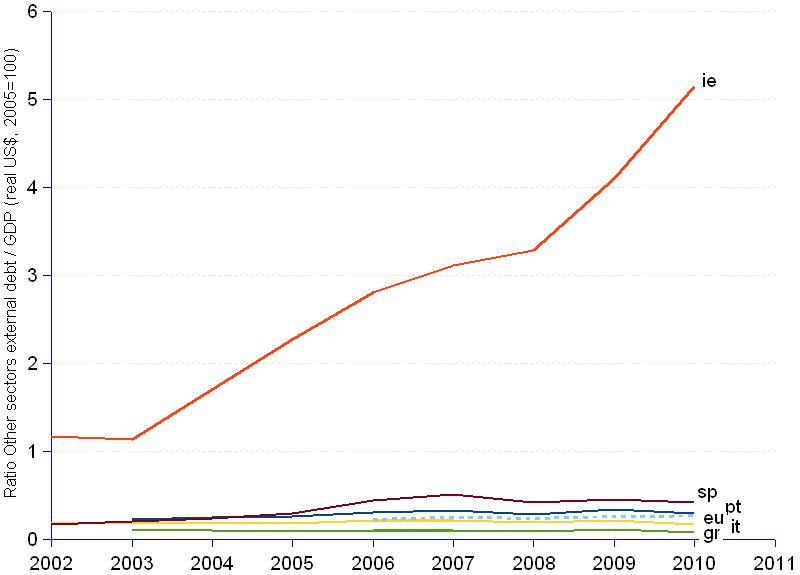

The "other sectors" item includes non bank financial corporations (e.g. financial intermediaries, insurance corporations, pension funds), non financial corporations, households and nonprofit institutions serving households. Although significantly lower than government or banks external debt, other sectors external debt represented in 2010 between 7% of GDP in Greece and 514% of GDP in Ireland. At Euro zone level, it amounted to 26% of GDP.

Other sectors external debt grew very fast until 2009, at average annual rates of 6% in Greece (12 years doubling time), 7% in Italy (10 years doubling time), 12% in Portugal (6 years doubling time), 26% in Spain (3 years doubling time), and 27% in Ireland (less than 3 years doubling time). The financial crunch that followed the 2008 crisis put the brakes on the PIIGS indebtedness process (negative change rates of -4% in Portugal or -23% in Greece), with the exception of Ireland.

A BIS¹ study of a set of advanced economies finds that non bank debt represented on average 167% of GDP three decades ago, and reached 314% of GDP by 2010. Of the 147 points increase, governments account for 49 percentage points, corporates for 42 percentage points, and households for the remaining 56 percentage points. Clearly, private external debt — for mortgage and for consumer credit — has been gaining overweight in the course of the last quarter of century.

A variety of explanations have been proposed for the upward trend. Many regulatory and business restrictions on banking activity and on loans have been waived since the 1970s. The 1990s decline in real interest rates, in a context of a relatively stable economic environment with low unemployment and low inflation rates, developed a feeling of confidence, inducing a propensity to borrow more heavily than reason would command. Fiscal policies supporting private borrowing through generous tax relief for mortgage interest payments, along with subsidies and guarantees to foster property ownership, also played a role in increasing debt, especially mortgages.

However, one should ask what led the banks to adopt more liberal lending policies, or governments and parliaments to pass laws in explicit support of the individual aspirations to own a home. A clue is provided by relating the long-term debt trend to the long-term income distribution trend. The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD)² has looked into income distribution and concluded that "Towards the end of the 2000s the income distribution in Europe was more unequal than in the average OECD country, albeit notably less so than in the United States (...) Large income gains among the 10% top earners appear to be a main driver behind this evolution." In other words, European top earners grab a bigger chunk of the available income, leaving only breadcrumbs to the small earners.

The main driver of rising income gaps has been greater inequality in wages and salaries, of which the spectacular rise in bankers’ and top executives’ pay is a fine illustration. Furthermore, many countries introduced generous tax cuts and exemptions for high-earners, and tried to partially compensate the lost taxes by an increasingly aggressive fiscal policy for the average and low earners. In face of shrinking tax revenue, governments decided to slash the benefit systems, thus rendering inefficient the instruments that had been designed to reduce inequalities decades ago.

OECD states that the income gap has risen even in traditionally egalitarian countries, such as Germany, Denmark and Sweden, from 5 to 1 in the 1980s to 6 to 1 today. The gap is 10 to 1 in Italy, Japan, Korea and the United Kingdom, and higher still, at 14 to 1 in Israel, Turkey and the United States. Indeed, the trend is clear in the United States. Employee compensation has been lagging significantly behind net dividends. The mean household income of the 5% top earners has been growing much faster than the median and other percentiles since 1990. Unfair fiscal policies reached such heights that billionaire Warren Buffett, demanded a substantial increase of taxes on the super-rich — naturally to no avail.

The widening income gap has a major drawback : it deprives millions of consumers of the buying power to sustain demand. How can consumption be pushed and the economy grow if most people cannot afford the goods ? In an anemic economy, how could dividends be paid to shareholders, and huge salaries and bonuses be granted to top earners that fail to meet their growth objectives ? The prevailing economic model commands that, by whatever means, the economy must turn out a growing output that consumers must eagerly buy.

During the last decade, the GDP of the Euro zone, after accounting for inflation, grew at the annual average rate of 4.9%, but the disposable income of the consumers did not follow. If consumers do not have the money, the solution is to persuade them to borrow from the banks — get the stuff now and pay later. If all goes well, they will work their lifetimes to pay interests and principal — a soft version of the slavery for debt, familiar to past civilizations. More likely, the system will run out of control and crash.

When the private sector becomes highly indebted, the economy can be badly damaged. The usual medicine of raising the cost of credit and making funding less available to would-be borrowers is a mere palliative. The only way out is to increase saving. But this will remain a mirage as long as the 1% to 5% of the population take most of the national income, and leave only scraps for the others.

¹ BIS Working Papers No 352, The real effects of debt, September 2011.

² OECD Economics Department Working Papers No. 952, Income Inequality in the European Union, 2012.

Ratio of Other Sectors External Debt to GDP (gross domestic product) | ||||||||||||||||||

Year¹ |

Portugal |

Ireland |

Italy |

Greece |

Spain |

Euro area |

||||||||||||

| Other sectors external debt ² | GDP ² | Other sect ext debt/ |

Other sectors external debt ² | GDP ² | Other sect ext debt/ |

Other sectors external debt ² | GDP ² | Other sect ext debt/ |

Other sectors external debt ² | GDP ² | Other sect ext debt/ |

Other sectors external debt ² | GDP ² | Other sect ext debt/ |

Other sectors external debt ² | GDP ² | Other sect ext debt/ |

|

| 2002 | 143 | 155 | 133 | 1.16 | 254 | 1,323 | 0.19 | 159 | 121 | 745 | 0.16 | 7,491 | ||||||

| 2003 | 37 | 172 | 0.22 | 191 | 168 | 1.14 | 280 | 1,602 | 0.17 | 23 | 205 | 0.11 | 185 | 939 | 0.20 | 9,054 | ||

| 2004 | 46 | 191 | 0.24 | 327 | 192 | 1.70 | 332 | 1,786 | 0.19 | 23 | 236 | 0.10 | 250 | 1,079 | 0.23 | 10,088 | ||

| 2005 | 48 | 191 | 0.25 | 458 | 202 | 2.27 | 321 | 1,778 | 0.18 | 21 | 240 | 0.09 | 323 | 1,130 | 0.29 | 10,132 | ||

| 2006 | 58 | 195 | 0.30 | 604 | 215 | 2.80 | 374 | 1,805 | 0.21 | 24 | 254 | 0.09 | 525 | 1,196 | 0.44 | 2,320 | 10,406 | 0.22 |

| 2007 | 70 | 218 | 0.32 | 757 | 244 | 3.11 | 419 | 1,991 | 0.21 | 27 | 287 | 0.09 | 684 | 1,357 | 0.50 | 2,877 | 11,625 | 0.25 |

| 2008 | 64 | 232 | 0.27 | 796 | 243 | 3.28 | 387 | 2,114 | 0.18 | 27 | 314 | 0.09 | 614 | 1,467 | 0.42 | 2,917 | 12,461 | 0.23 |

| 2009 | 72 | 214 | 0.34 | 830 | 202 | 4.10 | 401 | 1,926 | 0.21 | 32 | 294 | 0.11 | 604 | 1,336 | 0.45 | 2,890 | 11,316 | 0.26 |

| 2010 | 61 | 207 | 0.30 | 983 | 191 | 5.14 | 308 | 1,854 | 0.17 | 20 | 272 | 0.07 | 534 | 1,272 | 0.42 | 2,885 | 10,976 | 0.26 |

| 2011 | 66 | 986 | 310 | 19 | 529 | 3,113 | ||||||||||||

| Avge annual change rate | 7.5% | 4.7% | 4.6% | 22.8% | 4.6% | 20.4% | 2.2% | 4.3% | -1.8% | -2.5% | 7.0% | -6.0% | 17.8% | 6.9% | 12.6% | 6.1% | 4.9% | 4.2% |

| Avge annual change rate 2009-2011 | -4.2% | 9.0% | -12.1% | -23.1% | -6.4% | 3.8% | ||||||||||||

| ¹ All years show 4th Quarter values, except 2011 that is 3rd Quarter. | ||||||||||||||||||

| ² Billion real US$, 2005=100. | ||||||||||||||||||

Sources: JEDH for external debt, and World DataBank for GDP estimates.