What would you think of someone whose business generates gross margins of anything between 200% and a few thousands percent, and yet is persistently at the edge of bankruptcy and constantly demanding help ? In a competitive world where industries run on margins of 30% to 40%, such a performance can only be explained by utter incompetence, deception, or a reckless gambler's behavior.

PIIGS banks fit right in this frame. The ECB (European Central Bank) provides them with abundant monetary resources at a low refinancing rate of 1%. They can use the funds so acquired to finance their range of banking operations, including making loans to governments by buying risk-less AAA-rated government bonds at 2% or 3% (100% or 200% "spread" — the equivalent to the common gross margin), or somewhat riskier (nevertheless backed by EU and ECB) 10-year Greek bonds at 37% (a flabbergasting spread of 3,600%, achieved on 2 March 2012). One should think that business success under such soft conditions is a cinch. But no, not for banks — with gargantuan appetite, they devour gigantic rescue or bail-out funds provided by the taxpayer, and keep yelling for more.

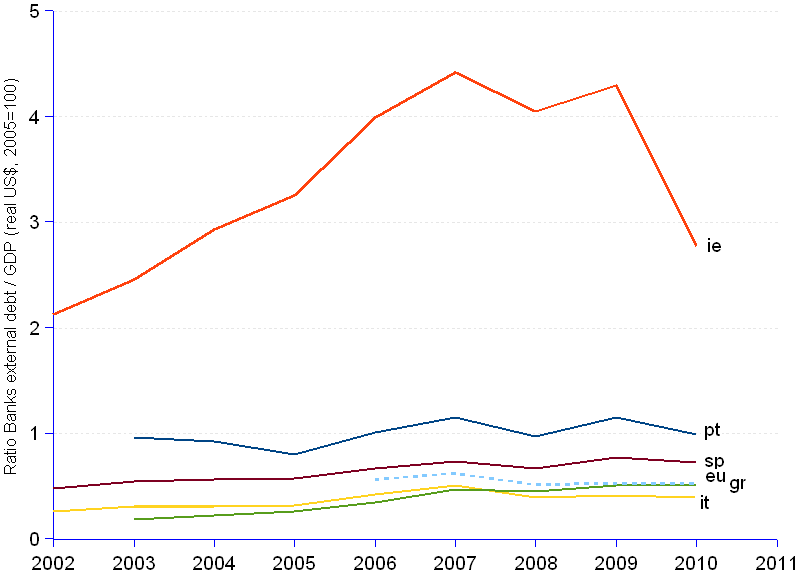

PIIGS banks are a permanent cause of concern. Foreign creditors' claims amount to the largest component of PIIGS external debt, $717 billion higher than — and at least as risky as — the government external debt. As shown in the chart, banks external debt varies from 40% of GDP in Italy to 277% in Ireland in 2010. The trend followed an upward path until 2009, at annual average rates of 3% for Portugal, 8% Ireland, 10% Italy, 21% Greece, and 11% Spain. Afterward, a significant deleveraging of PIIGS banks took place. In recent quarters, cross-border lending to banks located in the PIIGS countries declined sharply.

This trend reversal does not signal a health recovery, but rather the opposite, and may be explained by the lenders' lack of confidence. Indeed (1) :

The severity of the crunch led the ECB to launch two longer-term refinancing operations (LTRO) with a maturity of 36 months against a wider set of collateral (the first LTRO allotted EUR489 billion to 523 banks on 22 December 2011; the second LTRO allotted EUR530 billion to 800 banks on 1 March 2012). The ECB also halved the reserve ratio thus reducing the amount that banks must hold in the Eurosystem. European supervisory authorities further decided to temporarily accept additional credit claims as collateral in Eurosystem credit operations. Several governments developed a "bad bank" scheme to buy "toxic assets" (high-risk and over-valued assets) from the banks, with a view to reduce the level of risk on banks' balance sheets, therefore allowing them to increase their onward lending. Several banks in Portugal, Ireland, Greece and Spain had to be rescued by the state, through guarantee and recapitalization programs, or liquidated.

Altogether, public aid to the European banking system has been estimated at EUR4.5 trillion, or about 40% of Euro zone GDP (2). The amounts committed to PIIGS banks are out of proportion with the needs of other sectors, and the size of the economies : Portugal : 12%; Ireland : 319%; Italy : 4%; Greece : 18% and Spain : 24%, all as percent of the respective 2008 GDP (3).

Many banks that really should not be kept alive are being maintained afloat with the help of ECB and the European governments, at the cost of widening unemployment, impoverishing populations, de-industrialization, and consuming government resources that could advantageously be used in health, education, research, and overall well-being improvements.

The main economic rationale for granting state aid to financial institutions in crisis has been to avoid the collapse of banks causing the drying up of the credit pipeline, with serious problems for the wider economy. Since their meeting on 15 November 2008, the G20 (the group of 20 global economic powers) leaders stated their determination to boost growth and prevent further crises. A string of other G20 meetings followed in April and September 2009, February, October and November 2011, with further commitments to reinvigorate economic growth, create jobs, ensure financial stability, promote social inclusion and make globalization serve the needs of the people. So far the mission failed. Stagnation or outright recession prevail across the PIIGS area, entailing deepening unemployment and spreading poverty. Prospects remain dismal.

How did banks perform their function of lubricating the economy ? The provision by the ECB and the states of the above-mentioned liquidity facilities made access to market financing easier and released the banks' liquidity position, enabling them to soften the net tightening of credit (4), both for loans to non-financial corporations and for loans to households (for house purchase and consumer credit). The slowdown of the tightening of credit reflected on the terms and conditions, many banks allowing margins on average loans and collateral requirements to be less tighter.

Not great news, but it might not be too bad if the demand for loans were strong. Unfortunately, the net demand for loans to non-financial corporations has been dropping significantly, driven by a decline in the financing needs of firms for inventories and working capital, for internal financing, for issuance of securities, and in particular for fixed investment. Euro area banks also report a strong contraction in the demand for housing loans and consumer credit. To cut it short, the economy remains freezing cold, in spite of the trillions poured in the banks allegedly to warm the economy up.

While bank directors and executives watch their compensation climb back to stratospheric heights, while some of them are even co-opted to replace elected officials, one looks around and sees lots of losers struggling with higher taxes, lower incomes, shrinking social benefits, rising unemployment, and an economy falling apart. One can rightly call this the "casino economy" : a handful of guys make the bets, grab the money, and leave a crowd of losers alongside the road.

(1) BIS Quarterly Review, March 2012, International banking and financial market developments.

(2) Estimates of the total public aid to European banks vary widely. EU commissioner Almunia, in his conference "The third Future of Banking Summit" of 24 January 2012, states that "according to our figures ... EU governments have used a total of EUR1.6 trillion to rescue their banks... — equivalent to 13% of the Unionís GDP". In a DB paper No 13/2010, Stolz, of ECB and IMF and Wedow, of DB, evaluate the total commitment to financial institutions since October 2008 to end-May 2010 at 28% of 2008 Euro area GDP. 8 December 2011 : according to Arhold of the international law firm White & Case, between 1 October 2008 and 1 October 2011, the "around 290 decisions based on Art. 107(3)(b) TFEU [represented an] overall amount of state aid : EUR4506.5 billion (36.7% of EU GDP)".

(3) Estimates of state support to banks in % of 2008 GDP, October 2008 to May 2010, in : Deutsche Bundesbank, Extraordinary measures in extraordinary times — public measures in support of the financial sector in the EU and the United States, Discussion Paper Series 1: Economic Studies No 13/2010.

(4) ECB, The Euro area bank lending survey, 25 April 2012.

Ratio of Banks External Debt to GDP (gross domestic product) | ||||||||||||||||||

Year¹ |

Portugal |

Ireland |

Italy |

Greece |

Spain |

Euro area |

||||||||||||

| Banks external debt ² | GDP ² | Banks ext debt/ |

Banks external debt ² | GDP ² | Banks ext debt/ |

Banks external debt ² | GDP ² | Banks ext debt/ |

Banks external debt ² | GDP ² | Banks ext debt/ |

Banks external debt ² | GDP ² | Banks ext debt/ |

Banks external debt ² | GDP ² | Banks ext debt/ |

|

| 2002 | 143 | 283 | 133 | 2.12 | 339 | 1,323 | 0.26 | 159 | 356 | 745 | 0.48 | 7,491 | ||||||

| 2003 | 166 | 172 | 0.97 | 413 | 168 | 2.46 | 489 | 1,602 | 0.31 | 38 | 205 | 0.18 | 509 | 939 | 0.54 | 9,054 | ||

| 2004 | 176 | 191 | 0.92 | 562 | 192 | 2.93 | 557 | 1,786 | 0.31 | 53 | 236 | 0.22 | 607 | 1,079 | 0.56 | 10,088 | ||

| 2005 | 153 | 191 | 0.80 | 656 | 202 | 3.25 | 563 | 1,778 | 0.32 | 62 | 240 | 0.26 | 648 | 1,130 | 0.57 | 10,132 | ||

| 2006 | 196 | 195 | 1.00 | 861 | 215 | 3.99 | 764 | 1,805 | 0.42 | 88 | 254 | 0.34 | 794 | 1,196 | 0.66 | 5,855 | 10,406 | 0.56 |

| 2007 | 251 | 218 | 1.15 | 1,077 | 244 | 4.42 | 1,017 | 1,991 | 0.51 | 135 | 287 | 0.47 | 1,003 | 1,357 | 0.74 | 7,241 | 11,625 | 0.62 |

| 2008 | 225 | 232 | 0.97 | 984 | 243 | 4.05 | 835 | 2,114 | 0.39 | 142 | 314 | 0.45 | 982 | 1,467 | 0.67 | 6,415 | 12,461 | 0.51 |

| 2009 | 246 | 214 | 1.15 | 869 | 202 | 4.29 | 791 | 1,926 | 0.41 | 148 | 294 | 0.51 | 1,029 | 1,336 | 0.77 | 5,992 | 11,316 | 0.53 |

| 2010 | 204 | 207 | 0.99 | 530 | 191 | 2.77 | 735 | 1,854 | 0.40 | 141 | 272 | 0.52 | 921 | 1,272 | 0.72 | 5,737 | 10,976 | 0.52 |

| 2011 | 177 | 466 | 726 | 131 | 941 | 5,790 | ||||||||||||

| Avge annual change rate | 0.8% | 4.7% | 0.3% | 5.7% | 4.6% | 3.4% | 8.8% | 4.3% | 5.6% | 16.9% | 7.0% | 15.9% | 11.4% | 6.9% | 5.3% | -0.2% | 4.9% | -1.8% |

| ¹ All years show 4th Quarter values, except 2011 that is 3rd Quarter. | ||||||||||||||||||

| ² Billion real US$, 2005=100. | ||||||||||||||||||

Sources: JEDH for external debt, and World DataBank for GDP estimates.