![]() Global US drone strikes : Strike casualties | Number of strikes |

Global US drone strikes : Strike casualties | Number of strikes |

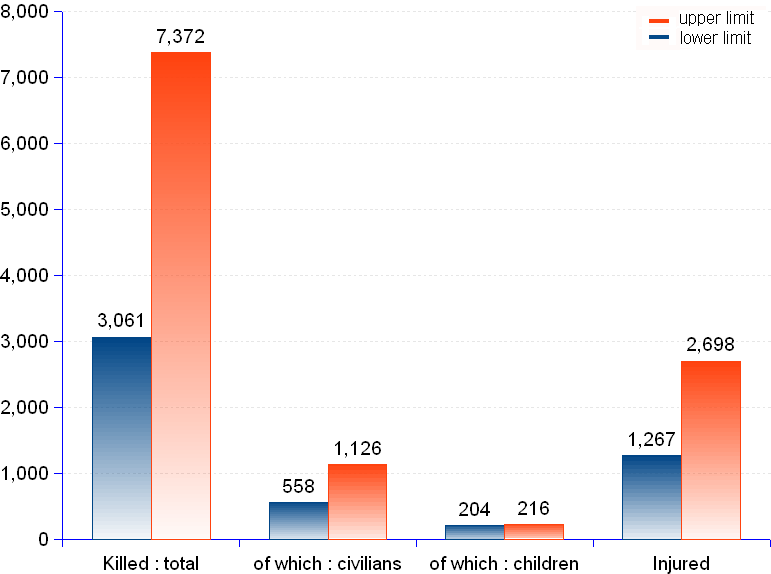

The United States global drone war is rapidly gaining momentum. On 24 January 2013, the US performed a minimum of 3,061 and possibly 7,372 state sponsored assassinations, including from 558 to 1,126 civilians, of which more than 200 children, by means of drone strikes in Pakistan, Yemen and Somalia. Although these attacks remain under the cloak of secrecy, Washington refusing to disclose any details to the press or the concerned state and private institutions, concerned independent observers have evaluated the total number of drone strikes to at least 407 and possibly 506, of which 362 in Pakistan, from 42 to 135 in Yemen, and from 3 to 9 in Somalia.

State sponsored assassinations, also known as "targeted killing"1 , "extrajudicial executions", or "summary executions", are anything but a novelty. History and stage drama offer plenty of instances for all tastes and preferences. What is brand new is that, while formerly such practices were universally condemned, even by the perpetrators themselves who vigorously denied the deeds, today's states cynically claim the right to carry out executions without proper judicial mandate, while maliciously trying to legitimize the unjustifiable with specious legal arguments. Israeli government set the trend by acknowledging in November 2000 the existence of a "targeted killings" policy, which between 2002 and May 2008 victimized at least 387 Palestinians — of these, 234 were the targets, while the remainder were collateral (an euphemism for innocent bystander) fatalities. However, as a rule with few exceptions, Israeli assassinations have taken place in the illegally occupied Palestinian territories, and were not purported to take the global scope that became the attribute of the US assassination program.

President G. W. Bush launched the cross-border murder program under the banner of the "Global War on Terror" soon after the attacks of 11 September 2001. The first reported assassination was perpetrated using a Predator drone in Yemen on 3 November 2002, killing Qaed Senyan al-Harithi, the suspected leader of the USS Cole bombing, in Aden, on October 2000.

In 2004 the program spilled over to Pakistan, in 2007 to Somalia, and is currently being extended to Mali and the Sahel region. With president Obama it made a quantum leap and became the privileged large scale process2 to take out alleged enemy lives across the world, in oblivion of national borders, of international law and of the universal right to life. Setting assassination targets became a regular function of the White House. President Obama currently keeps the program under his close scrutiny. He personally oversees the regular "Terror Tuesday" meeting, where plans are reviewed and decisions made according to the "Playbook" that spells out the procedural steps to follow and the people to involve, and which includes a "Disposition Matrix" gathering the available intelligence on the targets, their whereabouts, their linkages, and the assets to use to reach them. The president is where the buck stops : he is the ultimate custodian and the last resort decision maker of the secret "Kill List" that prioritizes the assassination targets.

If the US phraseology is to be believed, the "war on terror" was supposed to punish the authors of the September 11 attacks, and to prevent any relapses thereof. However, twelve years later, the US killings outnumber the victims of September 11, strongly suggesting that the process is all about revenge and intimidation, not justice and safety. Instead of temporary, it seems to be self-perpetuating — the more enemies are killed, the more remain to kill. As the Pakistani military chief reportedly said to Mike Mullen, the former chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff : "After hundreds of strikes, how could the US still be working its way through the 'top 20' list ?"

Drone assassination strikes are repulsively dirty, and raise numerous issues, political, military, legal, and philosophical that go beyond the scope of this note. A few highlights suffice to underscore the reasons why, not only such a program is a potent corrosive of peace, stability and freedom among national and international communities, but is also bound to produce counter-productive results for its initiators.

By improvising ad hoc legal rules to justify unlawful armed conflict practices, Washington undermines international and domestic law.

Currently, targeted killing is deemed legal under special circumstances in two situations : in an international armed conflict, and in a law enforcement operation. The legal rulings applicable to armed conflicts are found in the IHL (International Humanitarian Law, also known as War Law that includes the four Geneva Conventions of 1949 and their two Additional Protocols of 1977). Outside an armed conflict, targeted killing is ruled by human rights law and the state's domestic law. IHL has fewer process safeguards and is therefore more permissive than the latter. Hence the temptation to appeal to the armed conflict paradigm to whitewash criminal behavior patterns. By adopting the expression "war on terror", implying an armed conflict against a terrorist power, the Bush administration clearly chose to abuse the scope of the law.

IHL3 demands the parties involved in an armed conflict, whether or not international, to reduce human suffering by applying the "principle of distinction" between civilians and civilian objectives on one hand, and combatant and military objectives on the other hand, and by strictly refraining from direct, deliberate and indiscriminate attacks on civilians or civilian structures. IHL further prohibits acts of violence during armed conflict that do not provide a definite military advantage, that are disproportionate, i.e. entail higher risk of harming civilians in the vicinity, or are mere reprisal or punitive attacks. These rules apply equally to all parties to an armed conflict. It does not matter whether the party concerned is aggressor or is acting in self-defense, or if the party in question is a state or a rebel group.

The distinction between international and non-international armed conflicts is of utmost importance. International conflicts only exist between states, never between a state and a non-state group. The case of an armed conflict between a state and a non-state group is qualified as a non-international conflict. Combatants in an international conflict may be targeted at any time, any place, but civilians never. However, in a non-international armed conflict, states are allowed to directly attack civilians who "directly participate in hostilities"4 (DPH) — exclusively. It is moot what DPH specifically means. In any case, IHL rules that conducts such as general, financial or political support, advocacy, or any non-combat aid do not constitute direct participation, and do not make an individual subject to attack.

The war on terror, whatever it means to be, may well qualify as a war, but does not qualify as an international war, because "terror" is not a state. Now, could it be considered as a non-international war ? From a territorial viewpoint, a non-international war does not have to be limited to the state boundaries — it may extend to other state territories, and become a "transnational" war. The US war on terror is fought not only in Afghanistan (the only instance of a declared war between states), but also in Pakistan, Yemen, Somalia, and many other territories — including allied states such as Italy, Germany and others where covert, unlawful abductions and "extraordinary renditions" of suspected rebels (meaning, in Washington's parlance, secret extrajudicial transportation of unidentified detainees deprived of the basic protections of law) took place — thus resembling a "transnational" war. But this is by no means enough for the global war on terror to qualify as a non-international war, for at least three reasons. First, this war has been unilaterally waged by the US without the participation, not even the formal consent of the other concerned states. Second, It is debatable whether the operations by the non-state group went beyond isolated and sporadic acts of violence, thus satisfying the criterion of a minimum "threshold of intensity and duration" stipulated by the IHL. Thirdly, war laws provide that the non-state group must be an identifiable "party", not a loosely linked bunch of "associates" or individuals; it must have a minimum level of organization such that armed forces are able to identify an adversary; and it must hold such capabilities as an adequate command structure, and separate military and political commands. Obviously, the war on terror does not fit in the law — it is a moronic concept that even Washington tries to send back to the storeroom of the useless devices.

Excepting "direct participation in hostilities", attacks to civilians should be dealt with under the law enforcement framework, not the law of armed conflict. However, law enforcement standards do not make "targeted killing" legal because, unlike in armed conflict, killing cannot be the primary objective of an operation — the use of lethal force is legal if, and only if strictly and directly necessary to save innocent lives (e.g. law enforcers may resort to shoot down a suicide bomber after other means have failed). The right of the state to defend its citizens from terrorist threats is not challenged, but arrests, detentions and violence must observe defined legal frameworks, not ad hoc rulings. The blurred concept of "targeted killing" does not fit in any legal framework outside the law of international armed conflict. States cannot unilaterally extend the latter to situations that are essentially matters of law enforcement without emptying international law of its substance.

The White House elevated targeted killing to higher levels of illegality by approving not only "personality" strikes aimed at identified, high-value enemies, but also "signature strikes" that target individuals or groups neither legally nor factually identified, whose patterns of activity or vicinity may render suspicious without a shred of evidence of an imminent threat — for example, farmers packing a truck with fertilizer may be confused with bomb makers, rescuers bringing assistance to the people of a shelled village may be considered militant fighters in a training camp, or villagers gathering for a funeral may be seen as a militant planning meeting. The absence of criteria for targeting individuals, of substantive or procedural safeguards to ensure the legality and accuracy of the strikes, of accountability mechanisms such as ulterior retroactive and independent investigations, all these push even further the unlawfulness of the targeted killing. Insofar as such strikes hit a large proportion of civilians and take place far from areas recognized as being in armed conflict, they may constitute war crimes.

Since 2011, US citizens themselves became potential targets of the killing program. Formerly sheltered from assassination by the government through an array of robust statutes, including an executive order banning assassinations, a federal law against murdering other Americans abroad, and protections in the Bill of Rights namely the Fourth Amendment guarantee that a “person” cannot be seized unreasonably, and the Fifth Amendment provision that the government may not take a person's life "without due process of law", they have been made eligible to lethal attack by simple executive decision. An approximately 50-page memorandum5 by the Justice Department’s Office of Legal Counsel, completed around June 2010, has been deemed enough to supersede and overrule the constitutional and other legal guarantees. It first applied on 30 September 2011, in Yemen, when a drone campaign killed 4 people, among whom the US citizen Anwar al-Awlaki, a prominent al-Qaeda name on the White House "kill list" and another American, Samir Khan, apparently not on the list. A week later another drone strike killed al-Awlaki's 16-year-old son, also an American citizen. The fact that, six months before being killed, al-Awlaki was invited to the U.S. Embassy in Sana’a in order for the embassy to revoke his passport6 suggests that, despite their lawyers' convoluted quibbling, the US administration would have much preferred to be in a position to argue that the drone strike had targeted a foreign national, not an American citizen.

"Targeted killing" is self-defeating : it breeds more enemies than it destroys.

The widening span of US drone assassination campaigns since 2002 is evidence enough that the program, instead of becoming obsolete by achieving its goals, is failing to meet the objectives and must be continuously expanded to rise to the challenge of a fast swelling snowball of perceived threats. Year after year, drone strikes grow in number and in geographical reach. The terror they inspire fails to force the enemy to lie low. Like the mythological Hydra, each head severed becomes two. The program also gained unstoppable momentum : after targeting the Taliban and al-Qaeda top brass, it trickled to lower ranks, down to "foot soldier" level, and finally to anything that moves in the vicinity of the alleged militant whereabouts. It is becoming a self-raising, self-perpetuating leviathan.

Even more worrisome : whatever the rules the US asserts to deal with al-Qaeda and alleged "affiliates", they could also be invoked by other states or sub-states to apply to their own enemies. The elements of reason embodied in IHL and human rights law would totally yield to the sheer use of force. As other powers gain strength, one can wager that the justifications put forward by the US for pursuing their targeted killing program would in all likelihood not gain their endorsement, if other states were to invoke them.

"Targeted killing" extends "dirty hands" politics to implausible reaches.

A Machiavelli refresher should help : the ruler must keep in mind that the real world is what it is, not what it should be; to remain in power, the ruler must take a leave from high morals, and learn to be nasty, as well as to behave nastily if and when the situation so requires. The prescription looks as fresh in the 21th century as it did when originally written in the beginning of the 16th century. It sets the foundation of political realism, and would not be repudiated by today's influential American political guru Michael Walzer7, the inventor of "dirty hands" politics, or by most if not all the rulers of today's big powers.

It is easy to get one's hands dirty in politics and it is often right to do so, asserted Walzer. In politics, moral reasons weigh less than other considerations. In cases of "supreme urgency", it is legitimate to commit actions that in other circumstances would be criminal : ordering intensive bombing of civilian targets, torturing suspects, take out the lives of opponents or using state terrorism. In fact, adds Walzer, that is what political leaders are for, to take the required actions, even immoral ones.

The crux of the matter is the definition of "supreme urgency". Walzer's criteria are just two. First, the life itself of the members of the community is in jeopardy. Second, the "ongoingness" of the community's way of life is threatened. Under this view, in case of supreme urgency, the state can engage in a "just" war, is justified to use force without restraint, and may waive the rules of IHL and human rights law otherwise applicable to the use of force.

The tortuous legal advisers and speech writers of the White House and the Justice Department did not have to dig much deeper to find the justifications for the US assassination program. They just substituted "imminent risk" to "supreme urgency", "self-defense" to "just war", "killing of lawful wartime targets" to "assassination", added plenty of "terrorist threat" and of "American way of life", shook and served chilled — there you have the rhetorical drink that should help swallow all sorts of unlawful armed conflict conducts.

Notwithstanding, this line of reasoning subsumes the exemption of dirty hands for the powerful, as if their deeds could not be measured by the ordinary rule, as if they escaped the normal categories of morality, as if they were Nietzschean supermen beyond good and evil. But then, why should dirty hands exemption be available only to certain states, NATO states in this case, or even to those communities that have states, and not to sub-state communities, or even private groups and individuals ? What is the rationale that allows the US to follow the rule of necessity to save the life of their community members and to protect the continuity of their way of life, but refuses to legitimize rebel groups such as the Pashtun Taliban that claim similar rights to life and to the preservation of their way of life ? Clearly, US theories in support of the war on terror do not hold, and may lead to undesired and painful outcomes.

Casualties | ||

| Confirmed minimum | Possible | |

| Total killed | 3,061 | 7,372 |

| of which : civilians | 558 | 1,126 |

| of which : children | 204 | 216 |

| Injured | 1,267 | 2,698 |

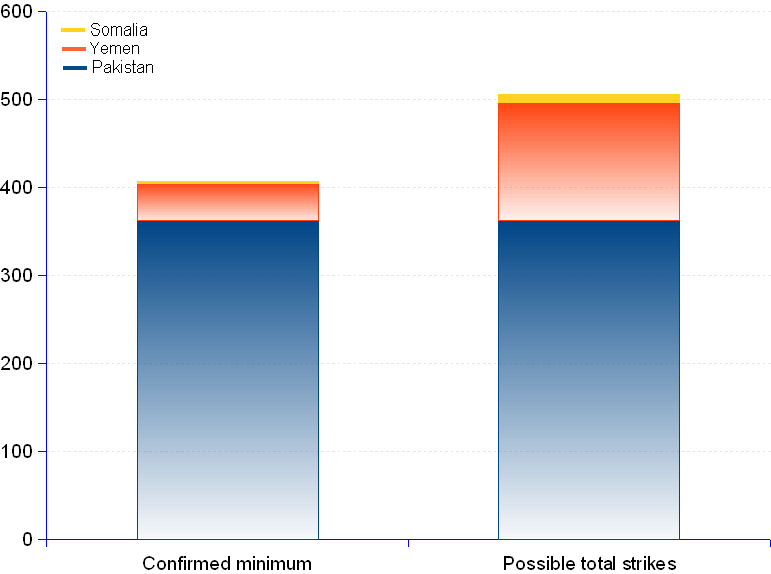

Since 2002, the United States launched a total of 407 confirmed, possibly 506 drone strikes in Pakistan, Yemen and Somalia. Of this total, 362 strikes hit Pakistan, from 42 to 135 Yemen, and from 3 to 9 Somalia. The momentum gained by this type of undeclared, remote-controlled, "PlayStation-like" war is illustrated by the 80%-plus average annual growth rate, corresponding to a doubling time of slightly more than one year.

US drone strikes | ||

Confirmed minimum | Possible total strikes | |

| Pakistan | 362 | 362 |

| Yemen | 42 | 135 |

| Somalia | 3 | 9 |

| Total | 407 | 506 |

| Average annual growth rate | 82.37% | 86.39% |

Sources: The Bureau of Investigative Journalism.